The Project Gutenberg EBook of Carriages & Coaches, by Ralph Straus

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Carriages & Coaches

Their History & Their Evolution

Author: Ralph Straus

Release Date: July 7, 2014 [EBook #46216]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CARRIAGES & COACHES ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Turgut Dincer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

BIOGRAPHICAL

ROBERT DODSLEY: POET, PUBLISHER AND PLAYWRIGHT

JOHN BASKERVILLE: A MEMOIR [with R. K. Dent]

NOVELS

THE PRISON WITHOUT A WALL

THE SCANDALOUS MR. WALDO

THE LITTLE GOD’S DRUM

THE MAN APART

PAMPHLETS

THE DUST WHICH IS GOD

5000 A.D.

| CARRIAGES & COACHES |

| THEIR HISTORY & THEIR EVOLUTION By Ralph Straus |

| FULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH REPRODUCTIONS FROM OLD PRINTS, CONTEMPORARY DRAWINGS & PHOTOGRAPHS |

| London: Published by Martin Secker at Number Five John Street Adelphi mcmxii |

PRINTED BY

WILLIAM BRENDON AND SON, LTD.

PLYMOUTH

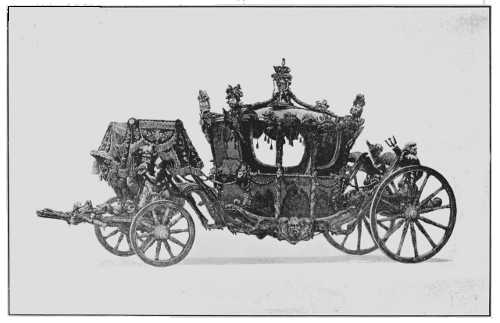

The State Coach of Great Britain

To

B. S. S.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE PRIMITIVE VEHICLE | 17 |

| II. | THE AGE OF LITTERS | 42 |

| III. | THE INTRODUCTION OF THE COACH | 56 |

| IV. | INTERLUDE OF THE CHAIR | 85 |

| V. | SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY INNOVATIONS | 109 |

| VI. | EARLY GEORGIAN CARRIAGES | 147 |

| VII. | THE WAR OF THE WHEELS | 176 |

| VIII. | THE AGE OF TRANSITION | 204 |

| IX. | INVENTIONS GALORE | 227 |

| X. | MODERN CARRIAGES | 255 |

| INDEX | 287 |

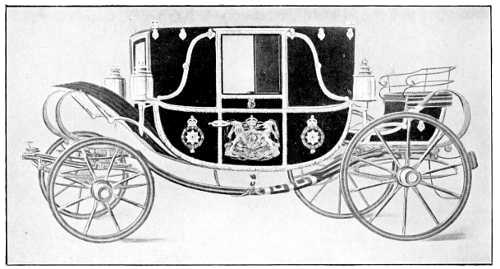

| The State Coach of Great Britain | Frontispiece |

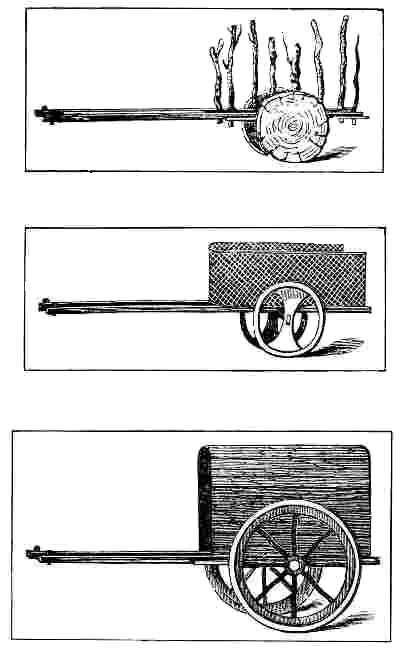

| Types of Primitive Carts | facing pagege20 |

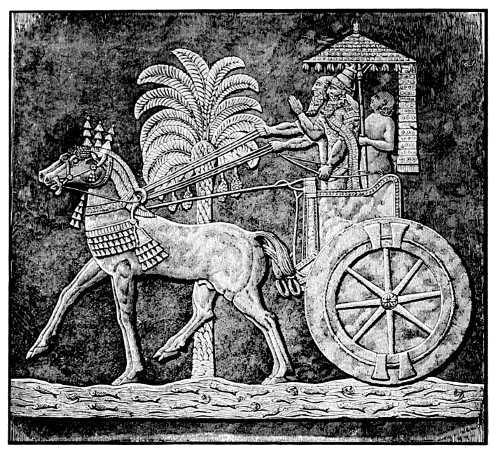

| Assyrian Chariot | faci”ngpa”gex22 |

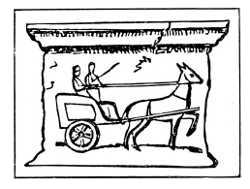

| Cisium | faci”ngpa”gex30 |

| Carpentum | faci”ngpa”gex30 |

| Pilentum | faci”ngpa”gex32 |

| Benna | faci”ngpa”gex32 |

| Fourteenth Century English Carriage | faci”ngpa”gex46 |

| Fourteenth Century Reaper’s Cart | faci”ngpa”gex46 |

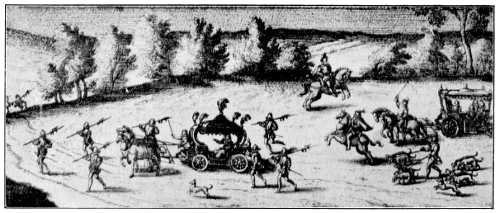

| Elizabethan Carriages | faci”ngpa”gex70 |

| Neapolitan Sedan-chair | faci”ngpa”ge100 |

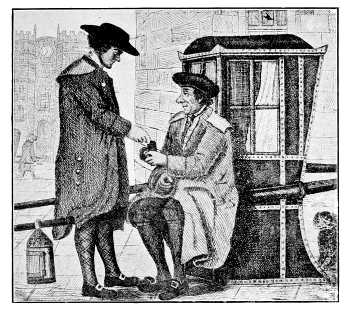

| The “Social Pinch” | faci”ngpa”ge104 |

| Sedans | faci”ngpa”ge104 |

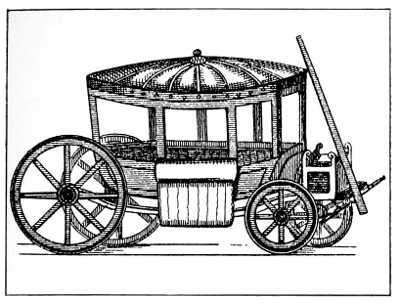

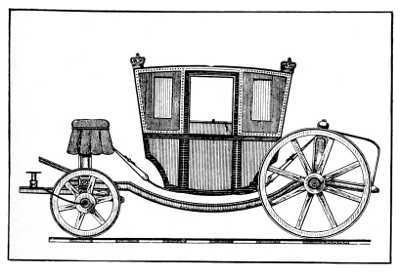

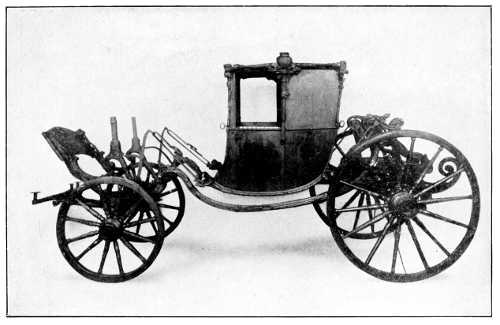

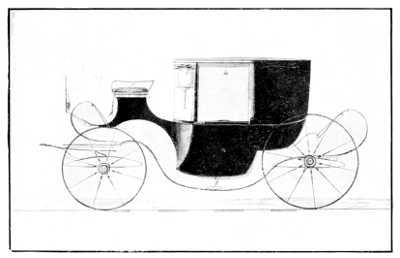

| Coach in the Time of Charles I | faci”ngpa”ge112 |

| Coach in the Time of Charles II | faci”ngpa”ge112 |

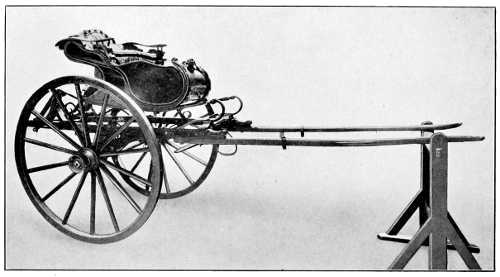

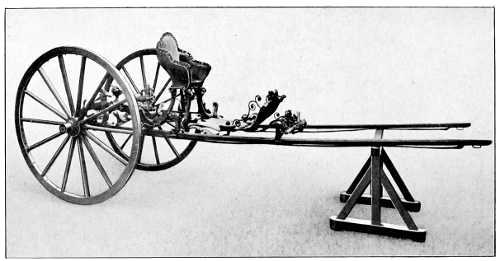

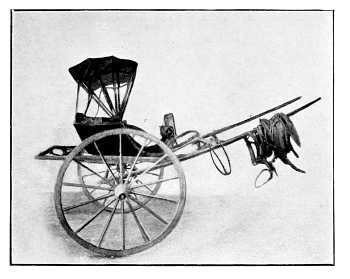

| Early French Gig | faci”ngpa”ge136 |

| Early Italian Gig | faci”ngpa”ge142 |

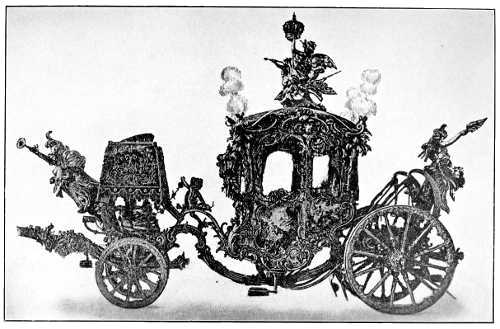

| The State Carriage of Bavaria | faci”ngpa”ge148 |

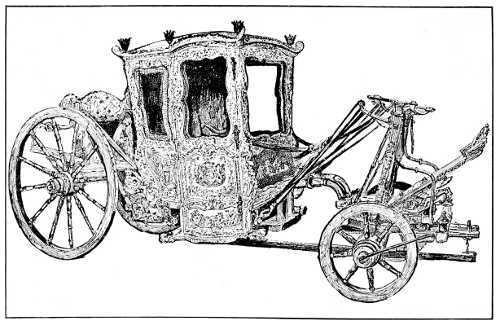

| The Darnley Chariot | faci”ngpa”ge152 |

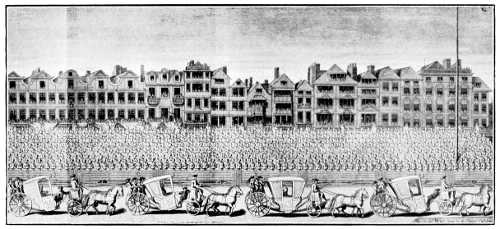

| Queen Anne’s Procession to the Cathedral of S. Paul | faci”ngpa”ge158 |

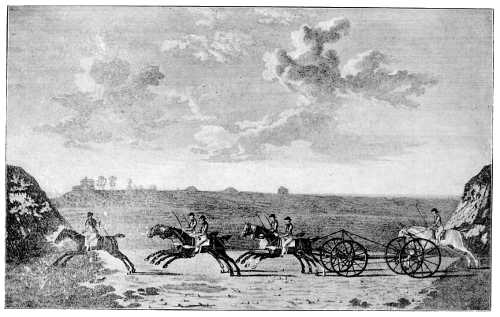

| “The Carriage Match” | faci”ngpa”ge190 |

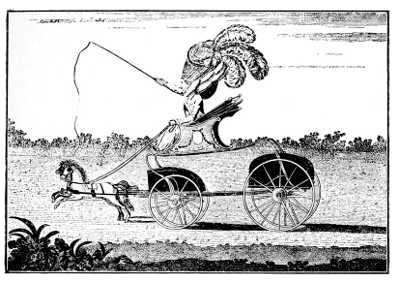

| “Phaetona, or Modern Female Taste” | faci”ngpa”ge196 |

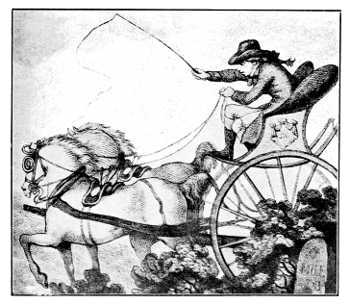

| “Sir Gregory Gigg” | faci”ngpa”ge196 |

| George III’s Posting Chariot | faci”ngpa”ge206 |

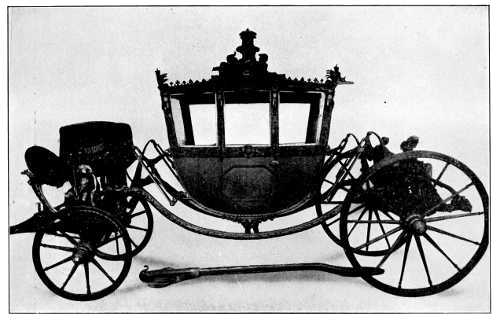

| The Lord Chancellor of Ireland’s Coach | faci”ngpa”ge208 |

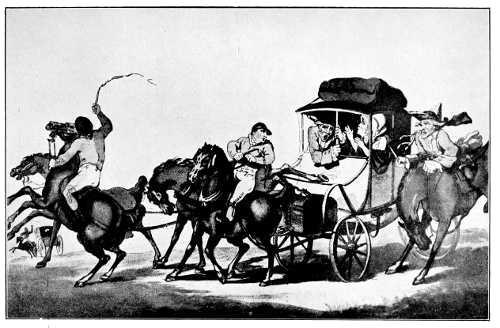

| “English Travelling, or the First Stage from Dover” | faci”ngpa”ge216 |

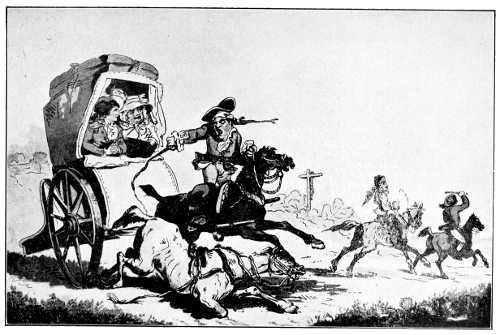

| “French Travelling, or the First Stage from Calais” | faci”ngpa”ge218 |

| Early American Shay | faci”ngpa”ge220 |

| English Posting Chariot | faci”ngpa”ge220 |

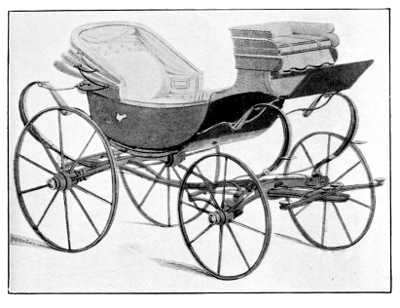

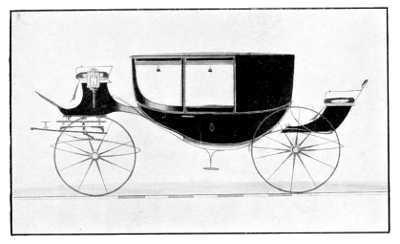

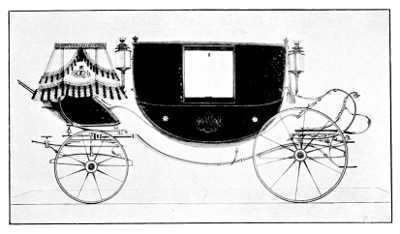

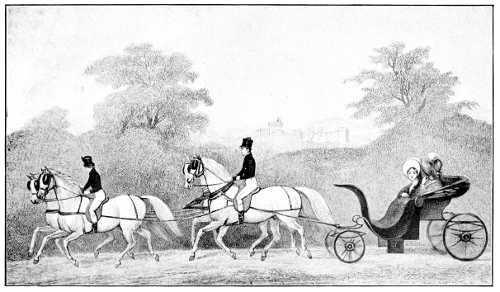

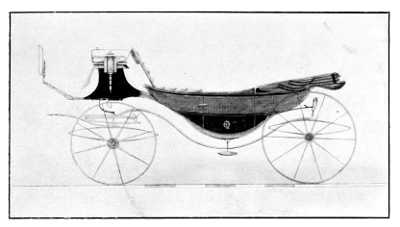

| 12Barouche | faci”ngpa”ge232 |

| Landaulet | faci”ngpa”ge232 |

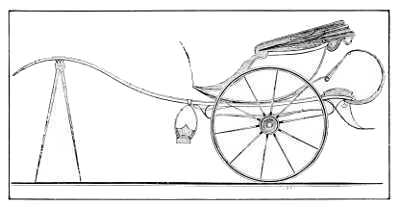

| Stanhope | faci”ngpa”ge234 |

| Tilbury | faci”ngpa”ge234 |

| Cabriolet | faci”ngpa”ge234 |

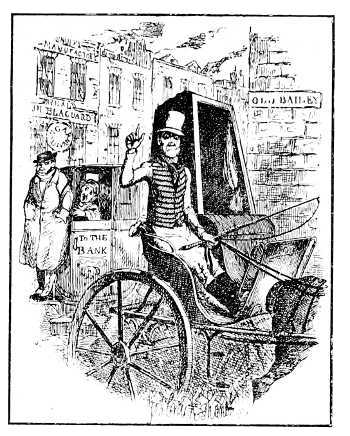

| “The Coffin-Cab | faci”ngpa”ge246 |

| London Cab of 1823 | faci”ngpa”ge246 |

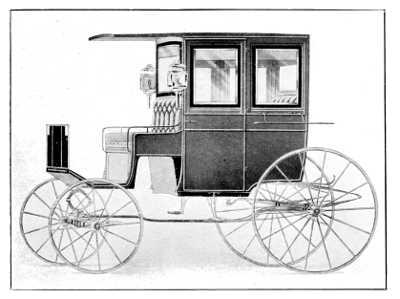

| Dioropha | faci”ngpa”ge252 |

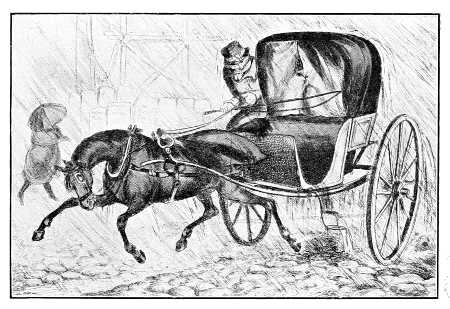

| Brougham in 1859 | faci”ngpa”ge252 |

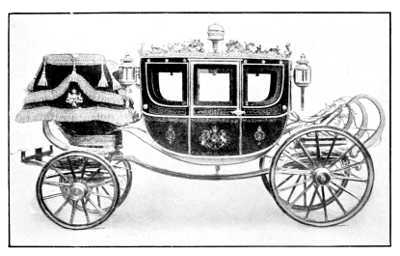

| Edward VII’s Coronation Landau | faci”ngpa”ge258 |

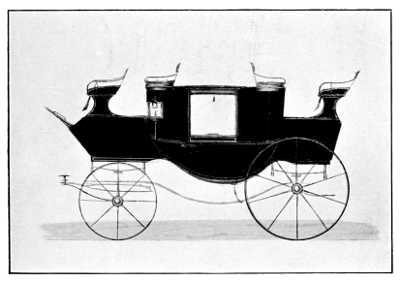

| Dress Coach, 1860 | faci”ngpa”ge260 |

| English State Carriage, 1911 | faci”ngpa”ge260 |

| “Princess Victoria in Her Pony Phaeton | faci”ngpa”ge266 |

| Canoe-shaped Landau | faci”ngpa”ge268 |

| Drag | faci”ngpa”ge268 |

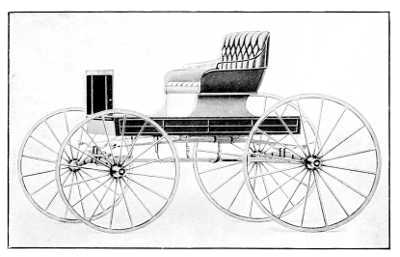

| Modern American Station Wagon | faci”ngpa”ge274 |

| Modern American Buggy | faci”ngpa”ge274 |

I AM not a coachbuilder. Though such a pronouncement will seem entirely superfluous to any coachbuilder who reads the following pages, it is not perhaps a wholly unnecessary remark. For, with one or two exceptions, such books upon the evolution or structure of vehicles as have been written have been the work of industrious coachbuilders. And I have not the least doubt that they are eminently the fit and proper folk to carry out any such task. It is a melancholy fact, however, that useful though these books may be to coachbuilders, they lack, again with one or two exceptions, any general interest to the layman. The language in which they are written is, to say the least, peculiar, and the authors have obviously had small training in the art of book-making. On the other hand, there is a whole library of books dealing with the old stage and mail coaches, with all the romance and adventure of the roads, packed with delightful anecdotes and personal reminiscences. But such books hardly touch upon the structure of the coaches themselves, and, so far as I know, there is no book entirely devoted to a non-technical description of carriages in general, based upon a chronological arrangement.

The nearest approach to such a book is Mr. G. A.14 Thrupp’s The History of Coaches, published in 1877, a meritorious undertaking from which I have freely quoted. Here, however, there are numerous gaps which I have endeavoured to fill, and the various lectures from which it was composed do not fit together so aptly as might be. As a whole, it is diffuse. Sir Walter Gilbey’s two books, Early Carriages and Roads and Modern Carriages, have also been of great assistance, but here, too, the ground covered is not so large as in the following pages. Other pamphlets and small books have appeared in this country, but seemingly owe a great deal of their information to Mr. Thrupp’s work. Indeed, I notice that some of the authors have been almost criminally forgetful of their inverted commas. For purely technical details there are, of course, many books and trade papers to consult; but with these I have not been concerned.

In the present book there are, indeed, large gaps, and it is not to be taken either as a manual of the art of coach-building or as a history of locomotion. It is merely a book about carriages, in which particular regard has been paid to chronological sequence, and particular attention to such individual carriages as have at all withstood the test of social history. And it is written by a layman who, until he enquired into the subject, had never looked at a carriage with any particular emotion. The result of his labours, therefore, is not meant for the expert, but for the general reader, who may have pondered over the various vehicles he has seen, and idly wondered how they may have been evolved.

Where possible, I have endeavoured to quote from15 contemporary authors and documents. Most of such quotations are now included in a carriage book for the first time.

I wish to thank the various publishers and authors who have given me permission to reprint illustrations of carriages in books published or written by them. Also I am obliged to Messrs. Maggs Bros., the well-known booksellers, for permission to photograph a rare print entitled The Carriage Match, in their possession.

RALPH STRAUS.

Badminton Club, August, 1912.

THE PRIMITIVE VEHICLE

IT has been suggested that although in a generality of cases nature has forestalled the ingenious mechanician, man for his wheel has had to evolve an apparatus which has no counterpart in his primitive environment—in other words, that there is nothing in nature which corresponds to the wheel. Yet even the most superficial inquiry into the nature of the earliest vehicles must do much to refute such a suggestion. Primitive wheels were simply thick logs cut from a tree-trunk, probably for firewood. At some time or another these logs must have rolled of their own accord from a higher to a lower piece of ground, and from man’s observation of this simple phenomenon must have come the first idea of a wheel. If a round object could roll of its own accord, it could also be made to roll.

Yet it is to be noticed that the earliest methods of locomotion, other than those purely muscular, such as walking and riding, knew nothing of wheels. Such methods depended primarily upon the enormously significant discovery that a man could drag a heavier weight than he could carry, and what applied to a man also applied to a beast. Possibly such discovery followed on the mere observation of objects being carried down the stream of some river, and perhaps a rudely constructed raft should be considered to be the earliest form of vehicle. From the raft proper to a raft to be used upon land was but a step, and the first land vehicle, whenever or wherever it was made, assuredly took a form which to this day is in common use in some countries. This was the sledge. On a sledge heavy loads could be dragged over the ground, and experience sooner or later must have shown what was the best form of apparatus for such work. As so often happens, moreover, in mechanical contrivances, the earliest sledge of which there is record—a sculptured representation in an Egyptian temple—bears a remarkable resemblance to those in use at the present time.1 Then, as now, men used two long runners with upturned ends in front and cross-pieces to unite them and bear the load. Such sledges were largely used to convey the huge stones with which the Egyptians raised 19their solemn masses of masonry and, incidentally, also as a hearse. In time, however, it was found that better results were obtained by the use of another and rather more complicated apparatus which had for its chief component—a wheel. This second discovery that to roll a burden proved an easier task than to drag it was fraught with such tremendous consequences as altered the entire history of the world.

It remained to find a better fulcrum than that afforded by the rough turf over which such logs, when burdened, were rolled. What probably followed is well described by Bridges Adams.2 “The next process,” he thinks, “would naturally be that of cutting a hole through the roller in which to insert the lever. The convenience of several holes in the circumference of the roller would then become apparent, and there would be formed an embryo wheel nave. It could not fail to be remarked also, that the larger the roller, the greater the facility for turning it, and consequently the greater the load that could be borne upon it.” Owing to the difficulty of using such large logs, he goes on to suggest, a time would come when it was found that a roller need not bear upon the ground throughout its length, but only at its extremities. So from the single roller would be evolved two rough wheels joined by a beam, square at first though afterwards rounded, upon which could be fixed a frame for the load.

Such axle and wheels would revolve together and keep the required position by means of pieces of wood which may be compared with the thole-pins of a boat. 20And it is a remarkable fact that until last century such primitive carts were in use in Portugal and parts of South America. The chief drawback to a vehicle of this kind is its inability to turn in a small space, and the pioneers, whoever they were, finally discovered the principle of the fixed axle-tree, the wheels revolving upon their own centre. So, “instead of fixing the cross-beam or axle in a square hole,” these pioneers “would contrive it to play easily in a round one of a conical form, that being the easiest form of adjustment.” Such a car as this, with solid wheels and a rude frame, was used by the Romans, and is still to be seen in parts of Chili. The next process in the evolution of the wheel doubtless followed upon the necessity of economising with large sections of wood, and there was finally invented a wheel made of three portions—a central pierced part, the nave, an outside circular piece, the rim or felloe, and two or more cross-pieces, joining the two, the spokes. Of these the felloes would tend to wear soonest, and a double set would be applied to the spokes, as was the case until recently in the ox-carts of the Pampas, or barcos de tierra, as they were called by the natives.

And indeed, the first carriages of which we have particular information, the chariots of the Egyptians and their neighbours, differ essentially from such primitive carts only in the delicacy and ornamentation of the carriage body.

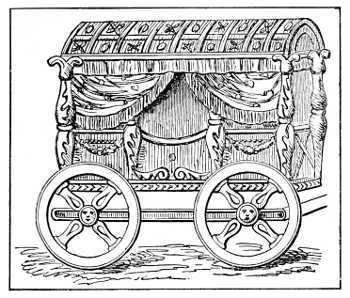

Types of Primitive Carts

Various vehicles are mentioned in the Bible, though one must be chary of differentiating between them merely because the translators have given them different names. Both waggons and chariots are mentioned in 21Genesis. Jacob’s family were sent to him in a waggon. Joseph rode in the second chariot of Pharaoh as a particular mark of favour. At the time of the Exodus, war-chariots formed an important part of the Egyptian army, and indeed, right through the various dynasties, there is an almost continuous mention of their use.3 “The deft craftsmen of Egypt,” says Breasted,4 “soon mastered the art of chariot-making, and the stables of the Pharaoh contained thousands of the best horses to be had in Asia.” About 1500 B.C. Thutmose III went forth to battle in “a glittering chariot of electrum.” He slew the enemy’s leader, and took captive their princes and “their chariots, wrought with gold, bound to their horses.” These barbarians also had “chariots of silver,” though this probably means that they were built of wood and strengthened or decorated with silver. At the dissolution of the Empire the Hittites had increased wonderfully in power, and it is told of them that they excelled all other nations in the art of chariotry. The Hittite chariot was larger and more heavily built than that of the Egyptians, as it bore three men, driver, bowman, and shield-bearer, while the Egyptian was satisfied with two. The enormous number of chariots used in warfare is shown by the fact that in the fourteenth century before Christ, when the Egyptians defeated the Syrians at Megiddo, nearly a thousand were captured, and against Ramses II the Hittites put no less than 2500 into the field.

“The Egyptian chariots,” says H. A. White,5 “were of light and simple construction, the material employed being wood, as is proved by sculptures representing the manufacture of chariots. The axle was set far back, and the bottom of the car, which rested on this and on the pole, was sometimes formed of a frame interlaced with a network of thongs or ropes. The chariot was entirely open behind and for the greater part of the sides, which were formed by a curved rail rising from each side of the back of the base, and resting on a wooden upright above the pole in front. From this rail, which was strengthened by leather thongs, a bow-case of leather, often richly ornamented, hung on the right-hand side, slanting forwards; while the quiver and spear cases inclined in the opposite direction. The wheels, which were fastened on the axle by a linch-pin secured with a short thong, had six spokes in the case of war chariots, but in private vehicles sometimes only four.6 The pole sloped upwards, and to the end of it a curved yoke was attached. A small saddle at each end of the yoke rested on the withers of the horses, and was secured in its place by breast-band and girth. No traces are to be seen. The bridle was often ornamented; a bearing-rein was fastened to the saddle, and the other reins passed through a ring at the side of this. The number of horses to a chariot seems always to have been two; and in the car, which contained no seat, only rarely are more than two persons depicted, except in triumphal processions.

Assyrian Chariot

(From Smith’s “Concise History of English Carriages”)“Assyrian chariots did not differ in any essential points 23from the Egyptian.7 They were, however, completely panelled at the sides, and a shield was sometimes hung at the back. The wheels had six, or, at a later period, eight spokes; the felloes were broad, and seem to have been formed of three distinct circles of wood, sometimes surrounded by a metal tyre. While only two horses were attached to the yokes, in the older monuments a third horse is generally to be seen, which was probably used as a reserve. The later chariots are square in front, not rounded; the car itself is larger and higher; the cases for the weapons are placed in front, not at the side; and only two horses are used. The harness differs somewhat from the Egyptian. A broad collar passes round the neck, from which hangs a breast ornament, the whole being secured by a triple strap under the belly of the horse. As in Egypt there are no traces visible; two driving-reins are attached to each horse, but the bearing-rein seems to be unknown. In addition to the warrior and the charioteer, we often see a third man who bears a shield; and a fourth occupant of the chariot sometimes appears.

“The Hittite chariots, as represented on Egyptian monuments, regularly contain three warriors. In construction they are plainer and more solid than the Egyptian, and the sides are not open. The chariots on Persian sculptures closely resemble the Assyrian.”

There is still preserved in the Archæological Museum at Florence an Egyptian chariot, a light, simple, two-wheeled affair with a single shaft and four spokes to the wheels. From the number of spokes it may be supposed that this particular chariot was not used in war. In New York, too, there is preserved the wheel 24of an Egyptian chariot found at Dashour. The particulars of this bear out Mr. White’s description. The wheel itself is three feet high, with a long axle arm, six spokes, tapering towards the felloe, and a double rim. “The six inner felloes do not meet as in modern wheels,” says Thrupp,8 “but are spliced one over the other, with an overlap of three inches.”

Artificial roads seem to have existed at an early period in Palestine, but the country was hardly suitable for vehicles, and one first hears of waggons in the flatter wastes of Egypt and the level plains of Philistia. Agricultural carts these were, though no doubt early used for passenger traffic. Some of these carts were most probably covered, though no coverings seem to have been fixed to the chariots. The Assyrians, however, occasionally took into their private chariots an attendant, who was provided with a covering shaped somewhat like a modern umbrella. This covering was held over the owner’s head, and was sometimes provided with a curtain which hung down at the back.

Details of the private carriages in use during these Biblical times filter through the chronicles. In Syria the merchants despatched by Solomon to buy chariots had to pay 600 shekels each for them. Solomon in his quest for luxury seems to have been the first man to build a more elaborate car than satisfied his contemporaries. One to be used on state occasions was built of cedar wood and had “pillars of gold.” Probably it was some form of litter. The number of private cars was increasing enormously in all these Eastern cities. The prophet Nahum in lamenting the future woes of Nineveh 25speaks of “the noise of the whip, and the noise of the rattling of the wheels, and of the prancing horses, and of the jumping chariots,” which will no longer bear witness to the city’s prosperity. The absence of wide roads, however, militated against great changes of form in the carriages, which maintained their simple shape until many centuries later.

The war-chariot (ἄρμα or δίφρος) of the early Greeks was curved in front, and loftier than that of the Egyptians. The entrance was at the back. It was never covered, but frequently bore a curious basket-like arrangement, the πείρινς, upon or in which two people could sit. The ἄντυξ, or rim, in most cases ran round the three sides of the body, but occasionally there was only a curved barrier in front. The body itself was often strengthened by a trellis-work of strips of light wood or metal. The barrier was of varying height; in some chariots it did not reach above the driver’s knee; in others it came up to his waist, but in war-chariots never higher than that. The axle was of oak, ash, elm, or even of iron, and precious metals, according to the legend, were used for the chariots of the gods. So of Juno’s car we read:—

The last line suggests an innovation which was certainly not followed for some considerable time.

The chariot in general was about seven feet long, and could be lifted by a strong man like Diomed. Indeed, it could be driven over the bodies of dead warriors. The pole sloped sharply upwards, and sometimes ended in the head of a bird or animal. It emerged either from the floor of the car or from the axle. Towards its end the yoke for the horses was fastened about a pin fixed into it. Though the Lydians used chariots with two or even three poles, the Greeks never had more than one; and as with the Egyptians, there were no traces. If the pole broke, the horses must have dashed away with part of it, leaving the chariot at a standstill. Occasionally, too, a third horse was used, upon which sat a postilion.

At a later period several Grecian carriages were in common use, though not in warfare. Representations of such cars are to be found on the Elgin Marbles. And, as was the case a dozen or more centuries afterwards, the carriage became the outward sign of luxury. It invariably appeared in the state processions, and was made the receptacle for the most gorgeous ornamentation. Gold, ebony, copper, ivory, and white lead were all used for this purpose, while the interiors of the cars were made comfortable with soft cushions and fine tapestries. They appeared, too, in great numbers at the famous chariot races, at which four or more horses were driven abreast. Often the same man was rich enough to possess more than one carriage. So we read of Xerxes changing from his ἄρμα to his ἁρμάμαξα, or state-carriage, at the end of a march. Besides these, there were also the ἀπήνη, a kind of family sociable, the ἅμαξα, a waggon, the κάναθρον, and the φορεῖον, or litter.

The ἁρμάμαξα was a large four-wheeled waggon, enclosed by curtains and provided with a καμάρα or roof. Four or more horses were required to draw it. It was so large that a person could lie in it at full length, and, indeed, on many occasions it acted the part of a hearse. By far the most extraordinary hearse ever built was a ἁρμάμαξα used to convey the body of Alexander the Great—himself the possessor of numerous carriages—from Babylon to Alexandria.

“It was prepared,” says Thrupp, “during two years, and was designed by the celebrated architect and engineer Hieronymus. It was 18 feet long and 12 feet wide, on four massive wheels, and drawn by sixty-four mules, eight abreast. The car was composed of a platform with a lofty roof supported by eighteen columns, and was profusely adorned with drapery and gold and jewels; round the edge of the roof was a row of golden bells; in the centre was a throne, and before it the coffin; around were placed the weapons of war and the arms that Alexander had used.”

The ἁρμάμαξα was also largely used by the ladies of Greece, who when they drove forth were careful to see that the curtains completely enclosed them. The ἅμαξα, also a four-wheeled waggon, was probably similar to the ἁρμάμαξα, though built upon a less imposing scale. The ἀπήνη was a still lighter carriage. It is described by Herodotus, and seems to have been a covered vehicle surrounded by silken curtains which could be pulled back when required. Its interior was generally furnished with cushions of goat leather. Two wheels were more frequent, but four were sometimes found. It was said that Timoleon, an old blind man, drove upon one28 occasion into the senate house and delivered a speech from his ἀπήνη. In some cases a two-wheeled carriage of this kind was not furnished with curtains, but enclosed in an oval-shaped covering of basket-work. Hesiod objected to such a conveyance because of its inability to keep out the dust. Little is known of the κάναθρον, but it was a Laconian car made of wood, with an arched, plaited covering, used chiefly by women. Doubtless it was little different from the ἀπήνη.

Coming to the Romans, we find a far greater variety of vehicles, though the descriptions that have come down are meagre and not particularly distinctive. That the Romans early realised the enormous importance, both military and otherwise, of carriages, is shown by their amazing roads. Such roads had never before been constructed. They were, says Gibbon, “accurately divided by milestones, and ran in a direct line from one city to another, with very little respect for the obstacles, either of nature or private property. Mountains were perforated, and bold arches thrown over the broadest and most rapid streams. The middle part of the road was raised into a terrace, which commanded the adjacent country, consisted of several layers of sand, gravel, and cement, and was paved with large stones, or, in some places near the capital, with granite.” Probably the most famous of these roads was the Appian Way, connecting Rome with Capua. It was wide enough, according to Procopius, who marched along it in the sixth century, for two chariots to pass one another without inconvenience or delay, a matter certainly not possible, for instance, in most of the Eastern cities at that time. And so, with the finest engineers the world29 had seen linking up various cities, cross-country travelling in a carriage, from being well-nigh impossible, became comparatively easy. Gibbon mentions in this connection the surprising feat of one Cæsarius, who journeyed from Antioch to Constantinople, a distance of 665 miles, in six days.

The Roman war-chariot, or currus, was practically the same as the Greek ἄρμα, though certain modifications were introduced. More than two horses were driven, and from their number came several words, such as sejugis, octojugis, and decemjugis, which sufficiently explain themselves. It appears, moreover, that the currus was occasionally driven by four horses without either pole or yoke, and it has been suggested that in such a case the driver probably stopped the car by bearing all his weight on to the back of the body, so that its floor would touch the ground, thus forming a primitive brake. Besides the currus, and even before their marvellous roads had been laid down, the Romans possessed other cars. The earliest of these seems to have been a long, covered, four-wheeled waggon, called arcera, which was mainly used to carry infirm or very old people. In this the driver sat on a seat in front of the body, and drove two horses abreast. Though the most ancient of the Roman carriages, the arcera, as seen on monuments, has a very modern appearance. In more luxurious times the lectica, a large litter, seems to have led to its gradual extinction.

The essedum, at one time very popular in Italy, was brought in the first place to Rome by Julius Cæsar. It was the war-chariot of the Britons, and was entirely unlike the Roman or Egyptian cars. The wheels were30 much larger, the entrance was in front and not at the back, there was a seat, and the pole, instead of running up to the horses’ necks, remained horizontal, and was so wide that the driver could step along it. The British charioteers could drive their cars at a very great rate, and were exceedingly agile on the flat pole, from the extremity of which they threw their missiles. The cars were purposely made as noisy as possible to strike dismay into the enemy’s lines. At times the wheels were furnished with scythes, which projected from the axle-tree ends, and helped to maim those unfortunate enough to be run down.9 Cicero, hearing good opinions of it, besought a friend to bring him a good pattern from Britain, and took occasion to add that the chariot was the only pleasing thing which that benighted country produced. The essedum speedily became popular in Rome, though not as an engine of war. Decorated and constructed of fine materials, it was the fashionable pleasure carriage. Curiously enough, however, the seat which had been so conspicuous a feature of the chariot in its native place was not used in Rome. The owner drove the essedum himself, and yoked two horses to the pole. There was some opposition to its use on the grounds of undue luxury, and a tribune who rode abroad in one was on that account considered effeminate. Seneca put the esseda deaurata amongst things quæ matronarum usibus necessaria sint. Emperors and generals used them as travelling carriages, and they were to be hired at regular posting-stations. A somewhat similar carriage, the covinus, was also in use in various countries at this date. This was covered in except in front; like 31the essedum, it had no seat for the driver, and in times of war it seems to have had scythes attached to the axle in the British fashion. Little, however, is known of it, and it may be dismissed here with a mere mention of its existence.

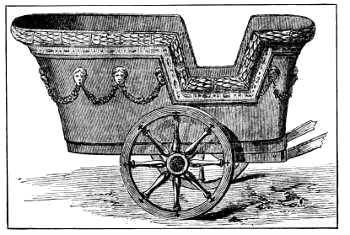

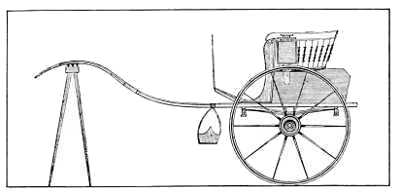

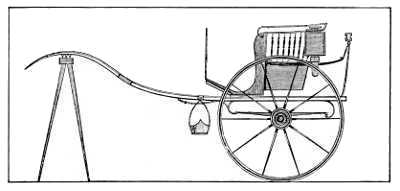

Cisium

The Primitive Gig

(From a Roman Inscription)

Agrippina’s Carpentum

(From a Roman Coin)

The essedum is of particular importance insomuch as it may be considered to be the prototype of all the vehicles of the curricle or gig type. The first of these in use amongst the Romans was the cisium, whose form is well shown on a monumental column near Treves. It was surprisingly like the ordinary gig of modern times. The body at first was fixed to the frames, but afterwards seems to have been suspended by rough traces or straps. The entrance was in front, there was a seat for two, and underneath this a large box or case. Mules were generally used to draw it, one, a pair, or, according to Ausonius, three—in which case a postilion sat on the third horse. They were built primarily for speed, and were in common use throughout Italy and Gaul, though the ladies, unwilling to be seen in an uncovered carriage, drove in other conveyances. The cisium on the whole must have been comfortable and light. Seneca admits that you could write a letter easily while driving in one. And in due course the new carriage became so popular that it could be hired, and the cisiarii, or hackney coachmen, could be penalised for careless driving. Indeed, so very modern were the Roman ideas upon the question of travel, that there were certain places at which the cisium was always to be found—a kind of primitive cab-rank.

Coming to the larger waggons and carriages, there were the sarracum, the plaustrum, the carpentum, the 32pilentum, the benna, the reda, the carruca, the pegma—a huge wheeled apparatus used for raising great weights, particularly in theatrical displays—and a mule-drawn litter, the basterna. Of these the sarracum was a common cart used by the country folk for conveying produce. It had either two or four wheels, and was occasionally used by passengers, though, as Cicero observed, as a conveyance the sarracum was very vulgar. It was not confined to Italy, but was common enough amongst those barbaric tribes against whom Rome was so often victorious. It was in sarraca, moreover, that the bodies were removed from Rome in times of plague. Rather lighter than this carriage, though heavy enough to our modern ideas, was the plaustrum,10 an ancient two or four-wheeled waggon of rude construction. This was, in its primitive form, just a bare platform with a large pole projecting from the axle; there were no supporting ribs at all, and the load was simply placed on the platform. Upright boards, or openwork rails, however, were used to make sides, and at a later period a large basket was fastened on to the platform by stout thongs. The wheels of the plaustrum were ordinarily solid, of a kind called tympana, 33or drums, and were nearly a foot thick. Such a cart was but a slow vehicle, and could turn only with great difficulty. It was drawn by oxen or mules, and like the sarracum was also used to carry passengers.11

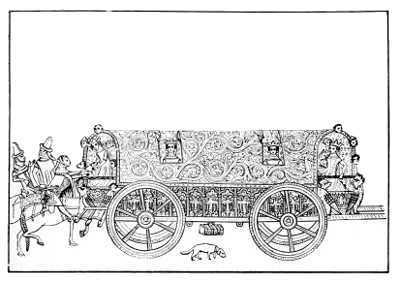

Pilentum

The State Carriage of the Romans

Benna

The carpentum, though two-wheeled, bore resemblance to the Greek ἁρμάμαξα. It had an arched covering. It was in use during very early times at Rome, though only distinguished citizens were privileged to ride in it. The currus arcuatus, given by Numa to the Flamines, was no doubt a form of carpentum, which was also the travelling carriage of the elder Tarquin. It seems to have been evolved from the plaustrum, being originally little more than a covered cart; but in the days of the Empire it became most luxurious, and was not only furnished with curtains of the richest silk, but seems to have had solid panellings and sculptures attached to the body. Agrippina’s carpentum, for instance, had fine paintings on its panels, and its roof was supported by figures at the four corners. Like the ἁρμάμαξα, it was also used as a hearse. Two mules were required to 34draw it. The pilentum was a carriage of a more official character. It may be called the state coach of the Romans—a four-wheeled becushioned car with a roof supported by pillars, but, unlike the carpentum, open at the sides. It was always considered to be the most comfortable of the Roman carriages, and may indeed have been hung upon “swing-poles” between the wheels. The social difference between the pilentum and the carpentum may be deduced from one of the many carriage laws passed by the Senate. The Roman matrons were allowed to drive in the carpentum on all occasions, but might use the pilentum only at the games or public festivals. Such “sumptuary laws” were constantly being passed, and a special vote was even required to enable the mother of Nero to drive in her carriage in the city itself. It was not until the fourth century A.D. that all such restrictions were banished.

Pliny mentions another carriage of imperial Rome—the carruca, which had four wheels and was used equally in the city and for long journeys. Nero travelled with great numbers of them—on one occasion with no less than three thousand. In Rome itself the fashionable citizen drove forth in a carruca that was covered with plates of bronze, silver, or even gold. Enormous sums were spent upon their decoration. Painters, sculptors, and embroiderers were employed. Martial speaks of an aurea carruca costing as much as a large farm. The carruca, indeed, may be said to correspond with the phaeton, which was so fashionable in England towards the end of the eighteenth century. As with the phaeton, so with the carruca—the higher it was built the better pleased was its owner. Various kinds of carruca existed.35 The carrucæ argentatæ were those granted by Alexander Severus to the senators. There is also mention of a carruca domestoria. Unfortunately, however, no contemporary representation of a carriage can definitely be said to be a carruca. Little enough, moreover, is known of the two other waggons, the reda and the benna. The reda was a large four-wheeled waggon used mainly to convey agricultural produce. It seems to have been brought into Italy from Wallachia. The benna was a cart whose body was formed entirely of basket-work. There is a drawing of it on the column of Antoninus at Rome. A similar vehicle persists to this day in Italy, South Germany, and Belgium, and bears a similar name.

Under the Empire, then, carriage-building flourished, particularly after Alexander Severus had put an end to all the older restrictions. Various forms of carriages were to be seen on the roads, and there was, as I have hinted, even an attempt at a spring. One of the carriages of this period is definitely described as “borne on long poles, fixed to the axles.” “Now a certain amount of spring,” says Thrupp, “can be obtained from the centre of a long, light pole. The Neapolitan Calesse, the Norwegian Carriole, and the Yarmouth Cart were all made with a view to obtaining ease by suspension on poles between bearings placed far apart. In these the seat is placed midway between the two wheels and the horse, on very long shafts, which are there made into wooden springs.” And in the old Roman carriages, he goes on to say, “the weight was carried between the front and hind axles, on long poles or wooden springs. The undercarriage of the later four-wheeled vehicles used by the Romans was, in all36 probability, the same as is in use at the present day, both in this country and on the Continent, and indeed in America, for the under-carriages of agricultural waggons.” Even with such splendid roads as the Romans possessed, however, the streets of their towns do not seem to have been very wide, and this must be one of the reasons for the early appearance of another kind of conveyance, the litter, which, during the dark ages, was practically the only carriage to be used.

These litters came from the East. The Babylonians in particular preferred to be carried about in a chair or couch rather than to be jolted in a carriage. Ericthonius, a lame man, is supposed to have introduced them into Athens, where they were known as φορεῖα or σκιμπόδια. Speedily they became popular, especially with the women. Magnificently decorated, the φορεῖον was constantly carried along the narrow streets, and on being brought over to Rome proved no less agreeable to the Romans. The lectica, or, as it was called at a later period, the sella, may in the first instance have been used to carry the sick, but in a short time became a common form of conveyance. This palanquin had an arched roof of leather stretched over four posts. The sides were covered by curtains, though at a later period it would seem that crude windows of talc were used. The interior was furnished with pillows, and when standing the litter rested upon four feet. Two slaves bore it by means of long poles loosely attached. In Martial’s time these lecticarii wore red liveries, and were sometimes preceded by a third slave to make way. Julius Cæsar restricted their numbers, and in the reign of Claudius permission to use them was granted only as a particular37 mark of the royal favour. Several varieties of litter appeared. The sella portatoria or gestatoria was a small sedan chair. Some, however, were constructed to hold two. The cathedra, which was probably identical with the sella muliebris mentioned by Suetonius, was mostly used by women. The basterna was a much larger litter, also used by women under the Empire, which was carried by two mules. In this carriage the sides might be opened or closed, and the whole body was frequently gilded.

A few other primitive carriages here call for mention. The Dacians, who inhabited parts of what is now Hungary, used square vehicles with four wheels, in which the six spokes widened towards the rims. The Scythians used a peculiar two-wheeled cart consisting of a platform on which was placed a conical covering, resembling in shape a beehive, and made of a basket-work of hazelwood, over which were stretched the skins of beasts or a thatching of reeds. When camping out these people would lift this covering bodily from the cart and use it as a tent. Much the same custom was followed by the wandering Tartars. “Their huts or tents,” says Marco Polo, “are formed of rods covered with felt, and being exactly round and nicely put together, they can gather them into one bundle, and make them up as packages, which they carry along with them in their migrations, upon a sort of car with four wheels.” “Besides these cars,” he continues, “they have a superior kind of vehicle upon two wheels, covered likewise with black felt, and so effectually as to protect those within it from wet during a whole day38 of rain. These are drawn by oxen and camels, and serve to convey their wives and children, their utensils, and such provisions as they require.” The same traveller described the carriages of Southern China. Speaking of Kin-sai, then the capital, he says, “The main street of the city ... is paved with stone and brick to the width of ten paces on each side, the intermediate part being filled up with small gravel, and provided with arched drains for carrying off the rain-water that falls into the neighbouring canals, so that it remains always dry. On this gravel it is that the carriages are continually passing and re-passing. They are of a long shape, covered at top, having curtains and cushions of silk, and are capable of holding six persons. Both men and women who feel disposed to take their pleasure are in the daily practice of hiring them for that purpose, and accordingly at every hour you may see vast numbers of them driven along the middle part of the street.” To this day such carriages as are here described can be had for hire in China, though in general they are of a smaller size. In some respects they resembled what is called in this country a tilted cart.

The Persians used large chariots in which was built a kind of turret from whose interior the warriors could at once throw their spears and obtain protection. One, taken from an ancient coin, is thus described by Sir Robert Ker Porter in his Travels in Georgia, Persia, and Ancient Babylon (1821):—

” ... a large chariot, which is drawn by a magnificent pair of horses; one of the men, in ampler garments than his compeers, and bareheaded, holds the bridle 39of the horses ... [which] are without trappings, but the details of their bits and the manner of reining them are executed with the utmost care. The pole of the car is seen passing behind the horses, projecting from the centre of the carriage, which is in a cylindrical shape, elevated rather above the line of the animals’ heads. The wheel of the car is extremely light and tastefully put together.”

Here, too, it is to be noticed that the driver is shown with his arms over the backs of the animals. In another chariot, which most probably was Persian, the body seems to be made of a “light wood, as of interlaced canes. Similar chariots are seen in the Assyrian bas-reliefs and others, somewhat resembling this, on Etruscan and Grecian painted vases. A chariot thus constituted must have been of extreme rapidity and of scarcely any weight.”12

The Persians also had an idol-car, which was a kind of moving platform, and their chariots were at one period armed with scythes. These scythes, generally considered to be the invention of Cyrus, do not seem to have hung from the axle-ends, as was the case in Britain, but from the body itself, “in order,” thinks Ginzrot, who wrote on these early carriages, “to allow the wheels to turn unobstructed. In this way,” he says, “the scythes had a firm hold, and could inflict more damage than if they had been applied to the wheels or felloes and revolved with them. Nearly all writers treating on this subject are of this opinion, and Curtius says: Alias deinde falces summis rotarum orbibus hærebant [thence curving downwards]. The scythes could 40easily have been attached to the body ... and, notwithstanding, it might be said they extended over the felloe, for Curtius said, not that the scythes revolved with the wheels, but hærebant.”13

Early Indian carriages were probably not very different from some of those now in use amongst the natives. The common gharry is certainly built after a primitive model. In this there are two wheels, “a high axle-tree bed, and a long platform, frequently made of two bamboos, which join in front and form the pole, to which two oxen are yoked.” In Arabia there was the araba, a primitive latticed carriage for women, which possessed “wing-guards”—pieces of wood shaped to the top of the wheels and projecting over them—a feature also to be found in the early Persian cars.

Taking these early carriages as a whole one may be inclined to feel surprise at the varieties displayed, yet there were not after all very great differences between them. They were two-or four-wheeled contrivances with a long pole in front, and it is only in mere size and decoration that discrimination can properly be made. “The Egyptians,” says Thrupp, “with all their learning and skill, appear to have made no change during the centuries of experience; as at the beginning, so at the end, the kings stand by the side of their charioteers, or 41hold the reins themselves. The Persians and Hindoos introduced luxurious improvements, and in lofty vehicles elevated the nobles above the heads of the people, and secluded their women in curtained carriages. The Greeks introduced no new vehicles, but perfected so successfully the useful waggon, that their model is still seen throughout Europe, without change of principle or structure. The Romans, on the other hand, in their career of conquest, gathered from every nation what was good, and, wherever possible, improved upon it.” After the fall of the Roman Empire, however, there was little further progress for several centuries. In the general retrogression, which, rightly or wrongly, one associates with those dark ages, the wheeled carriage, in common with a multitude of other adjuncts to civilisation, was to suffer.

THE AGE OF LITTERS

AS roadmakers, the Romans, if they can be said to have had successors at all, were succeeded by the monks. On the assumption that travellers were unfortunate people, as indeed they were, needing help, religious Orders were founded whose chief work was that of building bridges and repairing the roads. Other Orders likewise performed such tasks, though possibly for more selfish reasons, being as they were large owners of cattle, and immersed as much in agricultural as in theological occupations. So in many parts of Europe the Pontife Brothers, or bridge-makers, were to be found. There were also Gilds formed to repair the roads, such as the Gild of the Holy Cross in Birmingham, founded in the reign of Richard II, which “mainteigned ... and kept in good reparaciouns the greate stone bridges, and divers foule and dangerous high wayes, the charge whereof the towne of hitsellfe ys not hable to mainteigne.” In Piers the Plowman, too, the rich merchants are exhorted to repair the “wikked wayes” and see that the “brygges to-broke by the heye weyes” may be mended “in som manere wise.” The43 maintenance of the roads in England, says M. Jusserand,14 “greatly depended upon arbitrary chance, upon opportunity, or on the goodwill or the devotion of those to whom the adjoining land belonged. In the case of the roads, as of bridges, we find petitions of private persons who pray that a tax be levied upon those who pass along, towards the repair of the road.” So in 1289, Walter Godelak of Walingford is praying for “the establishment of a custom to be collected from every cart of merchandize traversing the road between Jowemarsh and Newenham, on account of the depth, and for the repair, of the said way.” Unfortunately for him—and doubtless he was no exception to the rule—the reply came: “The King will do nothing therein.”

Indeed the roads were in a truly abominable condition. As often as not, deep ruts marred what surface there had ever been, and here and there brooks and pools rendered easy passage an impossibility. There is a patent of Edward III (Nov. 20, 1353) which ordered “the paving of the high road, alta via, running from Temple Bar”—then the western limit of London—“to Westminster.” “This road,” says M. Jusserand, “had been paved, but the King explains that it is ‘so full of holes and bogs ... and that the pavement is so damaged and broken’ that the traffic has become very dangerous for men and carriages. In consequence, he orders each proprietor on both sides of the road to remake, at his own expense, a footway of seven feet up to the ditch, usque canellum,” and see to it that the middle of the road is well paved. In France matters 44were just as bad. “Outside the town of Paris,” runs one fourteenth-century ordinance, “in several parts of the suburbs ... there are many notable and ancient high-roads, bridges, lanes, and roads, which are much injured, damaged or decayed and otherwise hindered by ravines of water and great stones, by hedges, brambles, and many other trees which have grown there, and by many other hindrances which have happened there, because they have not been maintained and provided for in time past; and they are in such a bad state that they cannot be securely traversed on foot or horseback, nor by vehicles, without great perils and inconveniences; and some of them are abandoned at all parts because men cannot resort there.” Wherefore it was proposed that the inhabitants should be compelled, by force if necessary, to attend to the matter.

While, however, the wretched state into which the roads were being allowed to fall had a great deal to do with the almost total, though indeed temporary, extinction of the wheeled pleasure carriage in western Europe, there is another fact which must be taken into consideration in any endeavour to account for it. As will appear in a little, the renaissance of carriage-building in the sixteenth century was for a time retarded in various places by a widespread feeling of distrust against anything that could be thought to lead to an accusation of effeminacy. Laws were passed—as was the case, for instance, in 1294, under Philip the Fair of France—forbidding people to ride in coaches, and sharp comparisons were drawn by the satirists between the hardy horsemen of old and the modern comfort-loving individuals who lolled, or were supposed to loll—though how they could45 have done so in those springless monstrosities is past comprehension—in their gaudily decorated carriages. I would not insist upon the point, but it may be that in the reaction against such undue luxuries as had helped to bring ruin to the Roman Empire, carriages for that reason became unpopular. From which, of course, it would follow that the disappearance of the carriage led, in part at any rate, to the neglect of the roads, and such new roads as were made would be laid down primarily for the convenience only of the horsemen. The same thing applied also to the litters, though their popularity naturally followed merely upon the state of the roads.

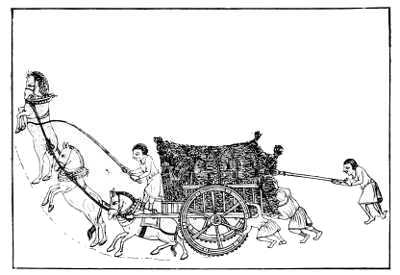

Before attempting to deal with these litters, it will be well to see what is known—it is not very much—of such wheeled carriages as there were at this time, and at the outset it is necessary to bear in mind that the old chroniclers used the word carriage in anything but its modern significance. To them a carriage was no more than an agricultural or baggage cart. Time and again you have accounts of this or that great man making his way, peaceably or otherwise, through some country, accompanied by numbers of carriages. These were simply his luggage carts, and although, as in earlier times, the cart, gaily ornamented, could very easily be converted into a pleasure carriage, it is important to remember the real meaning of the word. Such carts, in point of fact, were extremely common. In England they were generally square boxes made of planks borne on two wheels. Others, of a lighter pattern, were built of “slatts latticed with a willow trellis.” Their chief peculiarity was to be found in their wheels, which were46 furnished with extraordinarily large nails with prominent heads. Contemporary manuscripts give rough pictures of such carts. One of these is shown drawn by three dogs. One man squats inside, a second helps to push it from behind. A most interesting illustration in the Louterell Psalter—a fourteenth-century manuscript—shows a reaper’s cart going uphill. Here the two huge, six-spoked wheels with their projecting nails are clearly shown. The platform of the cart is strengthened by upright stakes with a cross-rail connecting them at the sides. The driver, standing over the wheels on the poles, is holding a long whip which is flicking the leader of three horses. Three other men are helping at the rear, and the stacks of wheat are held in position by ropes.

The earliest Anglo-Saxon carriage of which there is record belongs to the twelfth century. Strutt refers to a drawing in one of the Cottonian manuscripts, which represents a peculiar four-wheeled contrivance with two upright poles rising from the axle-trees, from which poles is slung a hammock. Such a chariot or chaer was apparently used by the more distinguished Anglo-Saxons when setting out upon long journeys. The drawing shows the figure of Joseph on his way to meet Jacob in Egypt, but is no doubt a correct representation of a travelling carriage in the artist’s lifetime. This hammock is interesting as being a primitive form of suspension, which may or may not have led to the later experiments in that direction.

Fourteenth Century English Carriage

(From the Louterell Psalter)

Fourteenth Century Reaper’s Cart

(From the Louterell Psalter)

A most luxurious English carriage of the fourteenth century is shown in the Louterell Psalter. This was obviously evolved from a four-wheeled waggon. Five 47horses, harnessed at length, drew it, a postilion with a short whip riding on the second, and another with a long whip on the wheeler. The tunnel-like body was highly ornamented, and its front decorated with carved birds and men’s heads. The frame of the body was continued in front as two poles, and underneath, hanging by a ring and looking rather ludicrous, is shown a small trunk. Women only appear in this carriage, the men riding behind it.

“Nothing,” remarks M. Jusserand, “gives a better idea of the encumbering, awkward luxury which formed the splendour of civil life during this century than the structure of these heavy machines. The best had four wheels; three or four horses drew them, harnessed in a row, the postilion being mounted on one, armed with a short-handled whip of many thongs; solid beams rested on the axles, and above this framework rose an archway rounded like a tunnel; as a whole, ungraceful enough. But the details,” he goes on to say, speaking of the carriage shown in the Louterell Psalter, “were extremely elegant, the wheels were carved and their spokes expanded near the hoop into ribs forming pointed arches; the beams were painted and gilt, the inside was hung with those dazzling tapestries, the glory of the age; the seats were furnished with embroidered cushions; a lady might stretch out there, half sitting, half lying; pillows were disposed in the corners as if to invite sleep, square windows pierced the sides and were hung with curtains. Thus travelled,” he continues with a touch of picturesqueness, “the noble lady, slim in form, tightly clad in a dress which outlined every curve of the body, her long, slender hands caressing the favourite dog or bird. The knight, equally tightened in his cote-hardie, regarded her with a complacent eye, and, if he knew good manners, opened his heart to his dreamy companion in long 48phrases like those in the romances. The broad forehead of the lady, who has perhaps coquettishly plucked off her eyebrows and stray hairs, a process about which satirists were indignant, brightens up at moments, and her smile is like a ray of sunshine. Meanwhile the axles groan, the horse-shoes—also heavily nailed—crunch the ground, the machine advances by fits and starts, descends into the hollows, bounds altogether at the ditches, and falls violently back with a dull noise.”

Other gaily decorated carriages, surprisingly like our modern vans, though on two wheels, are shown in Le Roman du Roy Meliadus, another fourteenth-century manuscript preserved in the British Museum, but only the richest and most powerful of the nobles could afford to keep them.

“They were bequeathed,” says M. Jusserand, “by will from one another, and the gift was valuable. On September 25, 1355, Elizabeth de Burgh, Lady Clare, wrote her last will and endowed her eldest daughter with ‘her great carriage with the coverture, carpets, and cushions.’ In the twentieth year of Richard II, Roger Rouland received £400 sterling for a carriage destined for Queen Isabella; and John le Charer, in the sixth [year] of Edward III, received £1000 for the carriage of Lady Eleanor—the King’s sister.”

These were fabulous sums, when it is remembered that an ox cost about thirteen shillings and a sheep but one shilling and five pence.

Now it may be that such a “great carriage” as is shown in the Louterell Psalter was identical with the whirlicote in which, according to Stowe, Richard II and his mother took refuge on the occasion of Wat Tyler’s rebellion.

“Of old time,” says this honest tailor, who himself witnessed the introduction of coaches into England, “coaches were not known in this island, but chariots or whirlicotes, then so called, and they only used of princes or great estates, such as had their footmen about them; and for example to note, I read that Richard II, being threatened by the rebels of Kent, rode from the Tower of London to the Mile’s End, and with him his mother, because she was sick and weak, in a whirlicote, the Earl of Buckingham ... knights and Esquires attending on horseback. But in the next year [1381] the said King Richard took to wife Anne, daughter to the King of Bohemia, that first brought hither the riding upon side saddles; and so was the riding in whirlicotes and chariots forsaken, except at coronations and such like spectacles.”

From this it would appear that the whirlicote (which may, as Bridges Adams suggests, have been derived from “whirling” or moving “cot” or house) was identical with the chariot or chaer. Unfortunately the translators of Froissart, who mentions the incident of Richard’s ride from the Tower, cannot agree upon the correct word to render the original charette. Charette, chariette, chare, chaer (Wicliffe), and char (Chaucer) all occur in the early chronicles, and there seems no means, if, indeed, there is any need, of differentiating between them. All were probably waggons modified for the conveyance of such passengers as could afford to pay highly for the privilege. One fact, however, suggests that there were at any rate two different kinds of carriages in England at this time, for we read that the body of Richard II was borne to its last resting-place “upon a chariette or sort of litter on wheels, such as is used by citizens’ wives who are not able or not allowed to keep50 ordinary litters.” With this in mind, it is difficult to agree with Sir Walter Gilbey when he says15 that the chare was a horse litter, though it is fair to add that he acknowledges an opposite view.

The charette is obviously the French form of caretta, which was the carriage in which Beatrice, the wife of Charles of Anjou, entered Naples in 1267.16 This vehicle is described as being covered both inside and without with sky-blue velvet powdered with golden lilies. Pope Gregory X entered Milan in 1273 in a similar carriage. The caretta was probably an open car “shaded simply by a canopy.” In the next century, the Anciennes Chroniques de Flandres, a manuscript belonging to 1347, shows an illustration of Ermengarde, the wife of Salvard, Lord of Rousillon, travelling in a four-wheeled conveyance remarkably like the ordinary country waggon of to-day.

“The lady,” says Sir Walter Gilbey, “is seated on the floor-boards of a springless four-wheeled cart or waggon, covered in with a tilt that could be raised or drawn aside; the body of the vehicle is of carved wood and the outer edges of the wheels are painted grey to represent iron tyres. The conveyance is drawn by two horses driven by a postilion who bestrides that on the near [left] side. The traces are apparently of rope, and the outer trace of the postilion’s horse is represented as passing under the saddle-girth, a length of leather (?) 51being let in for the purpose; the traces are attached to swingle-bars carried on the end of a cross-piece secured to the base of the pole where it meets the body.

“Carriages of some kind,” he continues, “appear also to have been used by men of rank when travelling on the Continent. The Expeditions to Prussia and the Holy Land of Henry, Earl of Derby, in 1390 and 1392-3 (Camden Society’s Publications, 1894) indicate that the Earl, afterwards King Henry IV of England, travelled on wheels at least part of the way through Austria.

“The accounts kept by his Treasurer during the journey contain several entries relative to carriages; thus on November 14, 1392, payment is made for the expenses of two equerries named Hethcote and Mansel, who were left for one night at St. Michael, between Leoban and Kniltefeld, with thirteen carriage horses. On the following day the route lay over such rugged and mountainous country that the carriage wheels were broken despite the liberal use of grease; and at last the narrowness of the way obliged the Earl to exchange his own carriage for two smaller ones better suited to the paths of the district.

“The Treasurer also records the sale of an old carriage at Friola for three florins. The exchange of the Earl’s ‘own carriage’ is the significant entry: it seems very unlikely that a noble of his rank would have travelled so lightly that a single cart would contain his own luggage and that of his personal retinue; and it is also unlikely that he used one luggage cart of his own. The record points directly to the conclusion that the carriages were passenger vehicles used by the Earl himself.”

It is to be noted that the carriage of the Lady Ermengarde was a Flemish vehicle. Flanders, indeed, seems to have shared with Hungary the honour of playing pioneer in carriage-building throughout the ages, and52 long after the general adoption of coaches in Europe, Flemish models, and also Flemish mares, were freely imported into the various countries.

Another carriage of this time is described in a pre-Chaucerian poem called The Squyr of Low Degree, in which the father of a Hungarian princess is made to say:—

The pomelles no doubt were “the handles to the rods affixed to the roof, and were for the purpose of holding on by, when deep ruts or obstacles in the road caused an unusual jerk in the vehicle.” One notices that lilies were apparently a common form of decoration on these early carriages, but it is to be regretted that the accounts in general are so scanty.

We come to the litters.

Of these the commonest, both in England and on the Continent, seem to have been modifications of the Roman basterna. Generally they were covered with a sort of vault with various openings. Two horses, one at either end, carried them. The great majority held only one person. Thrupp describes them in some detail.

“They were,” he says, “long and narrow—long enough for a person to recline in—and no wider than could be carried between the poles which were placed on either side of the horses. They were about four to five 53feet long, and two feet six inches wide, with low sides and higher ends. The entrance was in the middle, on both sides, the doors being formed sometimes by a sliding panel and sometimes simply by a cross-bar. The steps were of leather or iron loops, the latter being hinged to turn up when the litter was placed on the ground. The upper part was formed by a few broad wooden hoops, united along the top by four or five slats, and over the whole a canopy was placed, which opened in the middle, at the sides, and ends, for air and light.”

Isolated references to these horse-litters are scattered throughout the old chronicles, but afford meagre information. William of Malmesbury states that the body of William Rufus was placed on a reda caballaria, a horse-litter, the name of which suggests its origin. According to Matthew of Westminster, King John, during his illness in 1216, was removed from Swinstead Abbey to Newark in a similar vehicle, the lectica equestre. Generally, however, the horse-litter was reserved exclusively for women, men being unwilling to risk an accusation of effeminacy. So, in recording the death of Earl Ferrers in 1254, from injuries received in an accident to his conveyance, the historian is careful to explain that his Lordship suffered from the gout, which was why he happened to be in a litter at all.

As time passed, the litter rather than the wheeled carriage became the state vehicle. Froissart, writing of the second wife of Richard II, describes “la june Royne d’Angleterre” as travelling “en une litere moult riche qui etoit ordondée pour elle.” Margaret, the daughter of Henry VII, journeyed to Scotland, it is true, on the back of a “faire palfrey,” but she was followed by “one54 vary riche litere, borne by two faire coursers vary nobly drest; in wich litere the sayd queene was borne in the intryng of the good townes, or otherwise to her good playsher.” But on the Continent new improvements were being made in wheeled carriages, and when in 1432 Henry VI wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury and other high dignitaries of the Church, with regard to the widow of Henry of Navarre, he ordered them to place two chares at her disposal, rather than the litter to which one might have thought she would be entitled. Sir Walter Gilbey translates the word to mean a horse-litter, but Markland, in his paper on the Early Use of Carriages in England (Archæologia, Vol. XX), differentiates between the two, ascribing a more ceremonial use to the litter, and this seems to me to be nearer the truth. Both vehicles, for instance, are mentioned by Holinshed in his description of the coronation ceremony of Catherine of Aragon in 1509. The Queen herself rode in a litter of “white clothe of golde, not covered nor bailed, which was led by two palfreys clad in white damask doone to the ground, head and all, led by her footman. Over her was borne a canopie of cloth of gold, with four gilt staves, and four silver bells. For the bearing of which canopie were appointed sixteen knights, foure to beare it one space on foot, and other foure another space.” But the Queen’s ladies followed her in chariots decorated in red, and the same thing is true of Anne Boleyn, who in 1533 rode to her coronation in a litter, but was followed by four chariots, three decorated with red, and one with white. Such chariots probably resembled those to be described in the next chapter; the point to notice here is that they were55 being used now, and although the litters still continued until the time of Charles II—Mary de Medicis, the Queen-Mother of France, entered London in 1638 in a litter, though she had travelled from Harwich in a coach, and as late as 1680 “an accident happened to General Shippon, who came in a horse-litter wounded to London; when he paused by the brewhouse in St. John Street a mastiff attacked the horses, and he was tossed like a dog in a blanket”—the wheeled carriage once again became the vehicle of honour, and at the coronation of Mary in 1553 a chariot17 and not a litter was used by the Queen. This had six horses, and was covered with a “cloth of tissue.” Whatever its discomforts may have been, it cannot have been less dignified than the litter which it had, now for all time, supplanted.

INTRODUCTION OF THE COACH (1450-1600)

BOTH horse-litters and early wheeled carriages seem to have had some pretensions towards comfort. They afforded protection against the inclemency of the weather; there had been certain rude attempts at suspension, and the soft cushions helped to minimise the unpleasant joltings to which every carriage was liable. When, however, the renaissance of carriage-building occurred, people seem to have been but little more progressive than they had been centuries before. There were, as I have already hinted, still two factors which militated against a speedy adoption of such vehicles, more comfortable though they undoubtedly were, as now began to be made—the state of the roads, and the dislike of anything bordering upon the effeminate.

The roads had become no better. Even those most eager to welcome the new carriages must have been dismayed at the state of the country, not only in England, but in every European country. As one writer of the sixteenth century complains, the roads,57 “by reason of straitness and disrepair, breed a loathsome weariness to the passenger.” Nor is this writer a solitary grumbler: there are numerous complaints. In 1537 Richard Bellasis, one of the monastery-wreckers, was unable to proceed with his work: “lead from the roofs,” he reports, “cannot be conveyed away till next summer, for the ways in that countrie are so foule and deepe that no carriage [cart] can pass in winter.” Indeed, no one seems to have looked after the roads with any care, either in the fifteenth or the sixteenth century. Yet there were, in this country, repeated bequests for their preservation. Henry Clifford, Earl of Cumberland, a sufferer himself, left one hundred marks to be bestowed on the highways in Craven, and the same sum on those of Westmorland. John Lyon, the founder of Harrow School, gave certain rents for the repair of the roads from Harrow and Edgware to London. This was in 1592, and Lyon’s example was speedily followed by Sutton, the founder of the Charterhouse. There was, indeed, legislation of a kind, but in general the roads were in a terrible condition, and for a long time, so far as men were concerned, the saddle remained triumphant.

And for an even longer time continued that prejudice against carriages which led to the framing of actual prohibitive laws. Even women were occasionally forbidden the use of coaches, and there is the story of the luxurious duchess who in 1546 found great difficulty in obtaining from the Elector of Saxony permission to be driven in a covered carriage to the baths—such leave being granted only on the understanding that none of her attendants were to be allowed the same privilege.58 So, too, in 1564, Pope Pius IV was exhorting his cardinals and bishops to leave the new-fangled machines to women, and twenty-four years later Julius, Duke of Brunswick, found it necessary to issue an edict—it makes quaint reading now—ordering his “vassals, servants, and kinsmen, without distinction, young and old,” who “have dared to give themselves up to indolence and to riding in coaches ... to take notice that when We order them to assemble, either altogether or in part, in Times of Turbulence, or to receive their Fiefs, or when on other occasions they visit Our Court, they shall not travel or appear in Coaches, but on their riding Horses.” More stringent is the edict, preserved amongst the archives of the German county of Mark, in which the nobility was forbidden the use of coaches “under penalty of incurring the punishment of felony.” So, also, we have the case of René de Laval, Lord of Bois-Dauphin, an extremely obese nobleman living in Paris, whose only excuse for possessing a coach was his inability to be set upon a horse, or to keep in that position if the horse chanced to move. This was in 1550. In England there was a similar feeling of opposition. In 1584 John Lyly, in his play Alexander and Campaspe, makes one of his characters complain of the new luxury. In the old days, he says, those who used to enter the battlefield on hard-trotting horses, now ride in coaches and think of nothing but the pleasures of the flesh. The once famous Bishop Hall speaks bitterly of the “sin-guilty” coach:—

Possibly the same idea is to be found in the framing of a Parliamentary Bill of 1601 “to restrain the excessive use of coaches,” which, however, was thrown out. So again in 1623, the delightful though sadly biased water-poet, John Taylor, is lamenting the decadence of England, due, according to him, to the growing custom of driving in coaches.

“For whereas,” he says, “within our memories, our Nobility and Gentry would ride well mounted (and sometimes walke on foote) gallantly attended with three or four, score brave fellowes in blue coates, which was a glory to our Nation; and gave more content to the beholders, then [sic] forty of your Leather tumbrels: Then men preserv’d their bodies strong and able by walking, riding, and other manly exercises: Then saddlers was a good Trade, and the name of a Coach was Heathen Greek. Who ever saw (but upon extraordinary occasions),” he goes on to ask, “Sir Philip Sidney, Sir Francis Drake, Sir John Norris, Sir William Winter, Sir Roger Williams, or (whom I should have nam’d first) the famous Lord Gray and Willoughby, when the renowned George Earle of Cumberland, or Robert Earle of Essex? These sonnes of Mars, who in their time were the glorious Brooches of our Nation, and admirable terrour to our Enemies: these, I say, did make small use of Coaches, and there were two mayne reasons for it, the one was, that there were but few Coaches in most of their times: and the second is, they were deadly foes to all sloth and effeminacy.”

To Taylor, indeed, and probably to every one of his fellow-watermen, a coach was always a “hell-cart60” designed on purpose to put an end to his own most worthy calling. But less biased poets than outspoken Taylor gave tongue to an opposition which continued for nearly two centuries. Gay, for instance, looked on the vastly improved vehicle of his day as no more than an excuse for extravagant display:—

And again:—

Perhaps he is thinking of some personal inconvenience, rather than of mere unnecessary luxury, when he asks:—

And so late as 1770, the eccentric Lord Monboddo, who still maintained the superiority of a savage life, refused to “sit in a box drawn by brutes.” It is, of course, easy to magnify such opposition to coaches as followed on the grounds of mere luxury and display, but in the earlier history of the coach, to which we are now come, it is a factor which must by no means be neglected. The coach, like every other novelty, had to fight its way, and if one is inclined to believe, after reading such accusations as there are of the earliest coaches with their magnificent adornments and numerous attendants, that the owners altogether deserved the61 reproaches of their more Spartan fellows, it may be well to recall Macaulay’s words. In his sketch of the state of England in 1685, when coaches were still lavishly adorned, he says of them: “We attribute to magnificence what was really the effect of a very disagreeable necessity. People in the time of Charles the Second travelled with six horses, because with a smaller number there was great danger of sticking fast in the mire.” And what is true of 1685 is certainly true of 1585.

Buckingham is supposed to have been the first man to use a coach and six in this country, though this is by no means certain. Of him a well-known story apropos of this question of undue luxury is told. “The stout old Earl of Northumberland,” it runs, “when he got loose, hearing that the great Favourite Buckingham was drawn about with a Coach and six horses (which was wondered at then as a novelty, and imputed to him as a mastring pride) thought if Buckingham had six he might very well have eight in his Coach, with which he rode through the City of London to the Bath, to the vulgar talk and admiration.... Nor did this addition of two horses by Buckingham grow higher than a little murmur. For in the late Queen’s time there were no coaches, and the first [had] but two Horses; the rest crept in by Degrees as men at first venture to sea.”18 Yet what may have been true of Buckingham, whose love of luxury was notorious, need not have been true of those other owners of coaches, who were constantly travelling about the country.

Finally there is the other side of the question to be remembered, and, as M. Ramde quaintly points out in 62 his History of Locomotion, the very luxury which people so disliked had a beneficent effect; for “after the development of the use of carriages, and their frequent employment by the court and nobility, the liberty to throw everything out of the window became intolerable! Thus the carriage of luxury has been the cause of cleanliness in the streets.”

Now it must be understood that the coach proper differs from all earlier vehicles in being not only a covered, but also a suspended carriage. The canopy has given place to the roof, a roof, that is to say, which forms part of the framing of the body; and the body itself is swung in some fashion, however primitive, from posts or other supports. Further, it seems reasonable to suppose, on the analogy of the berlin and the landau—two later carriages which took their names from the towns in which they were first made—that the first coaches were built in a small Hungarian town then called Kotzee. Yet it is to be observed that Spain, Italy, and France, in the persons of various enthusiasts, have claimed the invention—their claims being mainly based on such similarities as may be observed between the real coach and the earlier cars and charettes.19 Bridges Adams, indeed, not to be outdone, hazards the suggestion that England might also be included in such a list by reason of her invention of the whirlicote, 63though he is obliged to admit that nobody knows exactly what a whirlicote was like. It is probably due to these patriotic gentlemen that several rather ludicrous suggestions have been made to explain the derivation of the word coach, which has a similar sound in nearly all European languages. Menange rashly suggests a corruption of the Latin vehiculum. Another writer puts forward the Greek verb ὀχέω, to carry. Wachten, a German, finds in kutten, to cover, a suitable explanation, and Lye produces the Flemish koetsen, to lie along. This last, perhaps, is the most reasonable suggestion of those unwilling to give the palm to Hungary, for not only were the Flemish vehicles well known before the introduction of the new carriage, but there is also some confusion, at any rate, in this country, between the two words coach and couch, both being found in the old account books. Even in the sixteenth century the word seems to have bothered people. There is an amusing reference to this point in an early seventeenth-century tract called Coach and Sedan Pleasantly Disputing, of which I shall have more to say in the next chapter.

“Their first invention,” says a character in this dialogue, “and use was in the Kingdome of Hungarie, about the time when Frier George, compelled the Queen and her young sonne the King, to seeke to Soliman the Turkish Emperour, for aid against the Frier, and some of the Nobilitie, to the utter ruine of that most rich and flourishing Kingdome, where they were first called Kottcze, and in the Slavonian tongue Cottri, not of Coucher the French to lie-downe, nor of Cuchey, the Cambridge Carrier, as some body made Master Minshaw, when hee (rather wee) perfected his Etymologicall dictionarie, whence we call them to this day Coaches.”