Produced by Al Haines.

TOM BURNABY

A STORY OF

UGANDA AND THE GREAT CONGO FOREST

BY

HERBERT STRANG

NEW EDITION

HUMPHREY MILFORD

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON, EDINBURGH, GLASGOW

TORONTO, MELBOURNE, CAPE TOWN, BOMBAY

REPRINTED 1922 IN GREAT BRITAIN

BY MORRISON AND GIBB LTD., EDINBURGH

MY DEAR JACK,

Your birthday has come round again--and here, with every good wish, is another book for your shelf. No mailed knights this time; our story is of the present day. Yet you shall find paynim hordes as many and as fierce as you please; yes, and chivalry itself, or I am much mistaken,--although we may not spell it with a capital C. For it is a theory of mine--"Old Uncle and his theories!" I hear you say!--that the spirit of chivalry is as much alive to-day as ever, and finds as free a scope. And if chivalry is, as I take it to be, the championing of the weak and the oppressed, no region of the world offers a wider field than Central Africa, where there is still ample work for the countrymen of Livingstone and Gordon. Some day, perhaps, you may yourself visit that land, and come back with as deep a sense of its glamour and pathos as the rest of us. Meanwhile, since even at Harrow the sky is not always clear, why not on some rainy afternoon pack up your traps and transport yourself in imagination to Uganda with Tom Burnaby? If you return with a certain stock of information about the land and its people--well, your old uncle will be all the better pleased. Not, of course, that this trip should be a reason for neglecting your football--or other duties!

HERBERT STRANG.

Contents

Illustrations

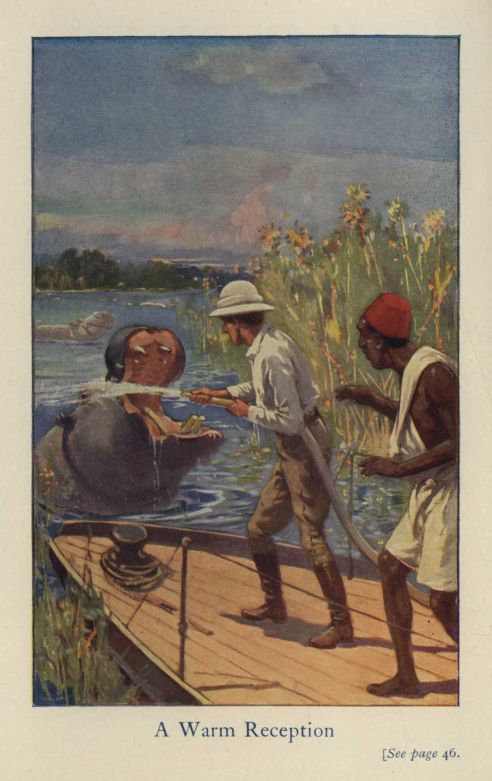

A WARM RECEPTION . . . . . . Frontispiece

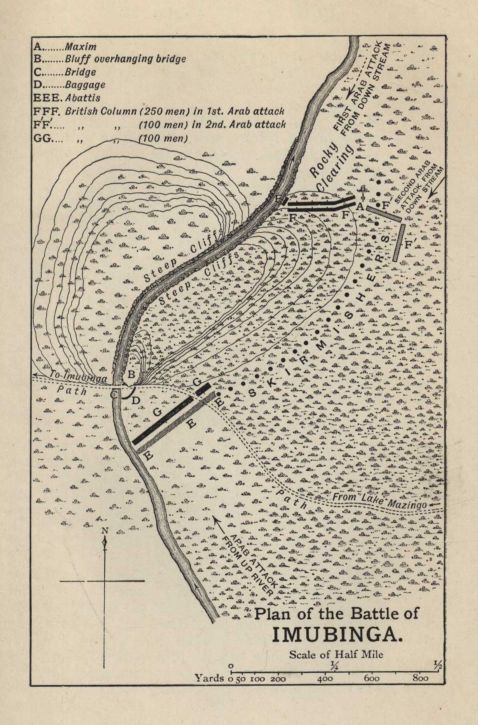

Plans

A belt of matted woodland. At the edge, three Belgian officers, in light uniform and white topee, lying prone, and peering cautiously out through glasses. Before them, a wide clearing, with a mud-walled town in the midst, and huge forest-trees beyond. Behind, a few score stalwart Bangala, strewn panting on the ground. Over all, the swarming sunlit haze of tropical Africa.

The gates stand open; peace reigns in Kabambari. But what is peace in Kabambari? Some hundreds of negro slaves are tilling sorghum in the cultivated tract outside the stockaded walls. Their chains clank as they move heavily down the field, dogged by an Arab overseer armed with rifle, scimitar, and whip. The pitiless sun, scorching their bent backs, blackens the scars left by the more pitiless scourge.

In the copse there is a whispered word of command; the negro soldiers spring silently to their feet, line up as best the broken ground permits, and then, at the heels of their white officers, charge out into the sunlight. No yell nor cheer, as they dash towards the open gate; the overseer, ere he can give the alarm, is bayoneted while his finger is on the trigger; the slaves, listless, apathetic, have scarcely time to realize their taskmaster's doom before the thin line has swept past them and through the gates. Then there is a sudden sharp crackle of musketry; cries of startled fear and savage triumph; and by ones and twos and threes, turbaned figures pour out of the far side of the town, a scanty remnant of the Arab garrison. One by one they drop as they cross the open; only a few gain the shelter of the forest. The heirs of Tippu Tib are broken and dispersed. The struggle has been long, the issue doubtful; but now, after years of stern fighting, the great Arab empire, founded upon murder, rapine, and slavery, is scattered to the winds. One thing only is wanting to make this last victory complete. Rumaliza, the Arab commander, Tippu Tib's ablest lieutenant, has escaped the net. Whether to live and build anew the dread fabric raised by his late chief; or whether to die in the gloomy depths of the Great Forest by starvation or disease, or by the poisoned arrow of the Bambute--who can say?

The Major--A New Friend--By Rail to Uganda--Dr. O'Brien Introduces Himself--The Major Orders a Retreat--Left Behind

A suit of boating flannels and a straw hat are no doubt a convenient, cool, and comfortable outfit for a July day on the Thames, but they fail miserably to meet the case on an average hot morning in Central Africa. So Tom Burnaby found as he walked slowly through Kisumu, stopping every now and again to mop his face and wish he were well out of it. If his dress had not betrayed him, his undisguised interest in the scene would in itself have bespoken the "griffin" to the most casual observer. The few Europeans whom he met eyed him with looks half of amusement, half of concern. One advanced as if to address him, then repented of the impulse and passed on.

Suddenly his attention was arrested by a noise ahead, gradually increasing in intensity as he approached. "The queerest noise you ever heard in your life," he wrote in a letter to a chum at home. "Imagine some score of huge ginger-beer bottles turned topsy-turvy and the fizz gurgling out, with a glug, glug, glug, and a sort of gigantic fat chuckle at the end,--then more glugging and chuckling, and chuckling and glugging. I was wondering what it meant, when suddenly I came to a huge shed, and then I saw the cause of all the row. About a hundred natives, as black as your hat, their skins shining like polished bronze, were working away at baggage and packages of all sorts, rolling up canvas, packing boxes and bales, tugging at ropes, and all the time jabbering and cackling and laughing and glug-glugging like a cageful of monkeys.

"I stood still and watched them for a minute, and then there was a sudden lull in the uproar, and I heard my old uncle's voice for the first time. There he was, the dear old chap, perched on a pile of ammunition-boxes, and the language he was using was evidently so warm that it was a wonder the whole show didn't blow up. I could only make out a word here and there, most of it was double Dutch to me; but whatever it was, it made those poor black fellows bustle for all they were worth. Then in the middle of his address the old boy suddenly caught sight of my unlucky self. You should have seen the expression on his face! He stopped as if a live shell had pitched into the shed; and--well, what happened then must keep till our next meeting. I could never do justice to the interview in a letter."

To say that Major John Burnaby was surprised at the sudden appearance of his nephew in Kisumu only feebly expresses his state of mind. After a few seconds of speechlessness, his feelings found vent in the deliberate exclamation:

"Well--I'm--hanged!"

Tom stood in front of him, looking very warm. There was another embarrassing silence.

"What do you mean by this?" were the major's next words.

"I really couldn't help it, Uncle Jack."

"Couldn't help it!" gasped the major.

"Oh well, you know what I mean! I saw in the papers that a column was going up to catch the beggars who killed Captain Boyes, and that you had got the job. 'Uncle Jack,' I thought, 'has got his chance at last, and I'm going to be there.' And here I am!"

"I see you are! And you mean to say you have left your work, thrown it all up, ruined your career, to come on a wild-goose chase like this? You'll go home by the next boat, sir."

"Don't say that, Uncle. I know it's sudden, but you see there was no time to lose. I couldn't write; I should never have got your answer in time; and you surely couldn't expect me to stop in a grimy engineering shop on the Clyde when my only uncle had got his chance at last! I must see it through with you, Uncle Jack."

"Must! must!" repeated the major. "Tom, I'm surprised at you--and annoyed, sir--seriously annoyed at your folly. The absurdity of it all! You can't join the expedition. It's against the regulations, for one thing; this is a soldier's job, and civilians would only be in the way. Besides, you're not seasoned; the climate would bowl you over in no time, and you're too young to peg out comfortably. What's more, you'd be no earthly use. Oh! I can't argue it with you," pursued the major, as Tom was about to protest; "you're demoralizing my men. Cut off to my bungalow, and keep out of mischief till I have done with them. Then I shall have something to say to you."

Tom looked pleadingly for an instant into his uncle's face, but finding no promise of relenting there, he turned slowly on his heel and walked away.

"So much for that! I was half afraid I'd catch it," he said to himself. "My word, isn't it hot!"

Tom was only eighteen, but he had already had disappointments enough, he thought, to last him a lifetime. Ever since he could remember, he had set his heart on being a soldier like his uncle Jack; but the sudden death of his father, a quiet country parson, had left him with only a few hundreds for his whole capital, and he had perforce to give up all ideas of going to Sandhurst. At this critical moment an opening offered itself in the works of an engineering firm on the Clyde, the head of which was an old school chum of his uncle's. It was Hobson's choice. He went to Glasgow, and there for a few months felt utterly forlorn and miserable. Then he pulled himself together, and began to take an interest even in the grimy work of the fitting-shop. He worked well, went through various departments, and was gaining experience in the draughtsman's office when he read one day in the paper that his uncle was appointed to the command of a punitive expedition in the Uganda Protectorate. The news revived his old yearnings; after one restless night he drew out enough to pay his passage and buy an outfit, and booked himself on the first P. and O. steamer for Suez.

Among his fellow-passengers the only one with whom he had much to do was a plump German trader, who joined at Gibraltar from a Hamburg liner. He amused Tom with his outbursts of patriotic fervour, alternating with periods of devotion to the interests of his firm. At one moment he was soaring aloft with the German eagle; at the next he was quoting his best price for pig-iron. Tom found him useful to practise his German on. He had always had a turn for languages; indeed, his only distinctions at school, besides his being the best bat in the eleven and a safe man in goal, were won in German and French. Naturally, he soon scraped acquaintance also with the chief engineer, and the pleasantest hours of the voyage out were those he spent in the engine-room, where he showed an unusually intelligent interest in the details of the machinery. He changed ship at Suez, and was heartily glad when, on awaking one morning, he caught sight of the white houses of Mombasa gleaming amid the dark-green bush.

The first thing he did on landing was to enquire the whereabouts of the expedition. He learned that it was fitting out at Kisumu, six hundred miles inland, on the shore of the Victoria Nyanza, and that he could reach the terminus at Port Florence by railway in two days. There being no train till next morning, he swallowed his impatience and roamed about the town. Amid the usual signs of Arab ruin and neglect he saw evidences of a new life and activity. He could not but admire the splendid harbour, in which a couple of British cruisers were lying at anchor; he climbed up to the old dismantled Portuguese fort, and examined every nook and cranny of it; he strolled about through the narrow, twisted streets, finding much to interest him at every step--grave Arab booth-keepers, sleek and wily Persians, lank Indian coolies, and negroes of every race and size in every variety of undress.

He put up for the night at the Grand Hotel. At dinner he was faced by an elderly gentleman with ruddy cheeks, side whiskers, and a shiny pate, who gave him a casual glance, but, with the Englishman's usual taciturnity, for some time said nothing. When, however, he had comfortably settled his soup, the old gentleman held his glass of claret to the light, looked at Tom over the rims of his spectacles, and said:

"Just out, sir?"

"Yes; I landed this morning."

"H'm! Government appointment, sir?"

"Well no, not exactly. The fact is, I've come out to see my uncle."

"H'm! Many boys do; hard up, I suppose," said the old gentleman under his breath. "Name, sir?"

"Burnaby--Tom Burnaby. My uncle is Major Burnaby of the Guides."

"Might have known it, h'm! you're as like as two tom-cats. Jack Burnaby's a fine fellow, sir; I know him. Fine country this. We made it a fine country. Ain't you proud to be an Englishman? 'Tis four hundred years or so since Vasco da Gama--heard of him, I suppose?--came ashore here on his famous voyage to India. To be exact, it was the year 1497. It was a fine place then; did a fine trade, sir. He didn't get backed up. No stamina in those Portuguese. Suffer from jumps, don't you know. Arabs got in; consequence, rack and ruin. Decay, sir; dry rot and mildew. We stepped in somewhere in the twenties, and then--stepped out again. Stupid! Now we've got our foot in, and begad we won't lift it again, or I don't know Joe Chamberlain. I know him. H'm!"

The old fellow's short snaps of sentences, and the little gasps he gave at intervals, rather tickled Tom.

"Yes," he continued, "the Sultan of Zanzibar in 1888 ceded it provisionally to the British East Africa Company. They were made definite masters of the place two years later, and also put in possession of a vast tract of country extending four hundred miles along the coast. H'm!"

At this Tom began to fear that he was in for a lecture, but he was reassured the next moment.

"Jack Burnaby's at Kisumu, six hundred miles up the line. There's a fine thing for you, now--this railway. Suppose you are going up to-morrow? We're coming on next week. Well, a word of advice, h'm! Don't go third-class. Nobody goes third-class. Blacks, you know--and lions. A lion boarded the train the other day, and swallowed two niggers in a winking. Strong-flavoured meat, h'm! Lions never touch first-class passengers--never tackled me! Well, I'll be glad to see Jack Burnaby again. He'll remember Ted Barkworth; yes, begad, and our little diversion in Tokio in 95. Now, sir, will you come and smoke a cigar with me? Don't smoke? Well, well, none the worse for it, at present, h'm! See you on the veranda, no doubt."

Mr. Barkworth went off to the smoking-room. As Tom got up, he noticed a red-covered book lying on the chair next to the one occupied by his talkative neighbour. He picked it up, intending to give it to one of the waiters, and casually turned over the leaves. The book opened rather easily at one place, and Tom, glancing at the page, saw: "The Sultan of Zanzibar in 1888 ceded it provisionally to the British East Africa Company. They were made definite masters of the place two years later, and also--" He read no farther; he had just recognized the passage which Mr. Barkworth had reeled off so glibly, and was chuckling at having discovered the source of the old man's information, when his glee was checked by a pleasant voice at his elbow saying:

"Excuse me, but have you seen a red-covered guide-book, left on one of the chairs?"

Tom straightened his face, and, turning, saw a pretty girl of some seventeen summers, looking very dainty and bewitching in her plain white frock. He closed the book, and held it out without a word.

"Oh, thank you!" said the girl. "Poor Father is always so careless."

And with a smile she flitted out of the room.

Later in the evening, when Tom strolled on to the veranda, Mr. Barkworth came up to him.

"H'm! come and let me introduce you to my daughter, sir. Lilian, Mr. Burnaby, nephew of my old friend Major Jack."

Lilian Barkworth gave Tom a friendly little nod and smile of recognition.

"My daughter, you know, Mr. Burnaby, wants to see the world--very restless, h'm! keeps her poor old father constantly on the trot. Two days in one place, then off we go: here to-day and gone to-morrow, h'm! But there's the admiral, I see--I know him; I must go and say how d'e do. Lilian, you may talk to Mr. Burnaby till nine o'clock. See you again, sir."

When he had gone over to speak to the admiral, Tom and Miss Barkworth looked at each other and smiled.

"Dear old Father! How deluded he is!" she said. "He firmly believes he scours the world for my benefit. I wouldn't undeceive him, but really, Mr. Burnaby, I would much rather live a quieter life. Now tell me, did he quote the guidebook?"

"Well, he did give me some historical information--"

"Ah! I thought so. I fancied you were smiling when you had the book in your hand. But he'll forget it all by to-morrow; he gets it up in five minutes and loses it in ten."

"Here to-day and gone to-morrow," suggested Tom, and the little quotation put them on good terms with each other, so that Tom was surprised to find how quickly the evening had flown when Miss Barkworth by and by held out her hand and said that her time allowance had expired.

He left Mombasa next morning before the Barkworths appeared. The journey on the single line of the Uganda railway was full of interest to him, impatient as he was to arrive at his destination. The train passed through some of the most wonderful scenery to be found anywhere on the face of the globe. Here were huge boulders, poised as though by some giant's hand, and the craters of long-extinct volcanoes; there, long stretches of open country, skirted by dense forests of acacias, banana-trees, and other tropical vegetation. Gazelles, giraffes, zebras, hartebeest sported in herds over the green plains; an occasional baboon was seen squatting on a branch; and here and there, by some lake or riverside, hippopotamuses and rhinoceroses wallowed and revelled in the shallows. Amid these signs of wild life appeared at intervals the straw huts of a native village; or a shanty, roofed with corrugated iron, marked the coming of civilization and trade: and then, towering high into the sky, rose the gigantic snow-capped form of Mount Kilimanjaro. The long journey came to an end at last, and Tom found his uncle--only to meet with sore disappointment, as already related.

He was still feeling rather downhearted as he walked towards Port Florence in the sweltering heat. It was by this time mid-afternoon, and every discreet person was indulging in siesta in the shade. Tom met no one but a few natives, dressed in little but hippo teeth and bead necklaces, and he was wondering how to find his way to the major's bungalow when his ear was caught by unmistakeable cries of pain. Turning a corner he saw a young black-follow writhing in the grip of a European in light but dirty attire, who held his victim by his woolly hair, and was belabouring his bare back with a whip of rhinoceros hide.

"Hi, you there? stop that!" cried Tom.

The man looked up sharply, gave the interrupter one scowling glance; and, seeing only a stripling, laid on again.

"D'you hear? Stop that!" shouted Tom, hurrying along till he came within arm's-length of the bully. "Drop that whip, or I'll knock you down."

The man, apparently a Portuguese of the low type that Portugal sends to her colonies, stared at him, spat out a curse, and raised his whip to strike again. That instant Tom's right arm shot out straight from the shoulder, and before the cruel thong could descend again, the brute found himself lying on his back in a pool of green mud. By the time he had picked himself up the negro had slipped away, and soon put enough ground between himself and his tormentor to make pursuit hopeless. Quivering with passion the man drew a knife from his belt and glared menacingly at Tom, who stood with hot brow and clenched fists ready to repeat the blow. But the sound of the altercation had drawn a few spectators to the spot, and, fearing the sure hand of British justice, the discomfited Portuguese furtively replaced his knife, and, with another ferocious look at Tom, slunk away.

"Fery goot, fery goot, my young friend," said a voice near Tom; "but you hafe soon forgot vun of my advice-vords."

"Oh, it's you, is it, Herr Schwab?" said Tom, turning and recognizing his fellow-passenger on the steamer.

"Yes, it is me," replied the German. "Vat hafe I said? I hafe said: Before all zings, step never in betveen ze native and ze vite man. Ze native are all bad lot, as you say. Now you hafe vun enemy, my young friend."

"Oh, that's all right! You couldn't expect me to look on and see that murderous brute ill-using the poor wretch?"

The German shrugged.

"Black is black, and business are business. Kindness all fery goot, courage equally all fery goot, but you should hafe--vat you call tact."

"Tact! Tuts! An ounce of common-sense to begin with," broke in another voice. "Where did you get that fool of a hat? Come along, come along."

Tom felt a firm hand on his sleeve, and, too much surprised to resist, he allowed himself to be dragged along by the new-comer, who did not stop till they reached the water's edge. There he stooped down and plucked a couple of large green leaves from a strange plant, and a moment later Tom found them flapping about his ears beneath his hat.

"There, now you'll do," said his captor. "The idea of coming out and practising boxing under an African sun in a three-and-sixpenny straw hat! Sure an' if I hadn't met you you would have been food for jackals in twelve hours. Thank your stars you were taken in hand by Dr. Corney O'Brien. And now, who are you?"

The little man with the keen gray eyes and pleasant mouth looked up at Tom and frowned.

"A Burnaby, by the powers! And I never knew the major had a family. Ah, but you're a Burnaby, plain enough, whatever they christened ye--Tom, Dick, or Harry!"

"Right first shot, Doctor," said Tom with a smile. "I'm Tom Burnaby, at your service. Will you be good enough to direct me to my uncle's bungalow?"

"Will I? Indeed I will. Come along."

Talking all the time, the little doctor led Tom in the direction of Port Florence. A few minutes' walking brought them to the major's bungalow, a one-story building of wood, raised a few inches from the ground, with a neatly-thatched roof overhanging a sort of veranda. Tom was soon stretching his legs luxuriously in one of his uncle's comfortable chairs, and scanning the walls hung with small-arms, hunting trophies, and a few choice engravings.

"Ah, this is nice!" he said. "Can I have a drink, Doctor?"

"To be sure. What'll you have? Your uncle's burgundy is good. I can recommend it."

"Really, a drink of water would do me best just now."

"Very well. Here, Saladin, cold water."

The major-domo, a tall muscular Musoga, appeared with a carafe of sparkling water.

"Lucky you're this side of the counthry," the doctor went on. "For ten years, d'ye know, I never wance touched water. 'Twas in Ould Calabar, where most of the dry land is swamp, and the rest mud, and the rule is, drink and die. But what are ye doing out here, my bhoy?"

Tom told his story, the doctor breaking in every now and then with sympathetic little ejaculations.

"'Tis hard luck; to be sure it is," he said, when Tom had told him of his uncle's blunt refusal to allow him to accompany the expedition. "But the major's right, you know, and I couldn't venture any attempt to persuade'm. We call'm Ould Blazes, you see."

"I couldn't ask you to, Doctor. I've come on a fool's errand, and have only myself to blame. I must just make the best of it. What is to be is to be."

"That's right, now. And sure here's the major himself."

"Pf! pf!" blew Major Burnaby, as he entered the room. "Glad that's over for the day at any rate. You've got the young scamp in hand, I see, Corney. Tom, untwizzle that ringer; I must tub before I do anything else."

Tom looked up to where his uncle was pointing, above his head, and saw the wire of an electric bell twisted round a bracket on the wall. He got up and pressed the button, and the major-domo appeared.

"Tub, Saladin," said the major. "And look here, this is my nephew; put him up a bed and do him well."

"All right, sah! all same for one," returned the negro cheerfully.

In a few moments the major could be heard splashing and gasping in the next room, and ere long he returned in mufti, looking cool and comfortable in a suit of white ducks and a silk cummerbund. He asked the doctor to stay to dinner, and Tom sat listening eagerly to his seniors' conversation, and admiring his uncle's thorough grasp of even the minutest details of the expedition.

It was to set out, he learned, in three or four days' time, some three hundred and fifty strong, from Port Florence, and was to cross the Nyanza in steam launches. The only Europeans besides the major and Dr. O'Brien were Captain Lister and a subaltern, the non-commissioned officers being trustworthy Soudanese. Their objective was the village of a petty chief, about a hundred and fifty miles west of the Nyanza, who had revolted against British authority, and in concert with the remnants of an old Arab slave-dealing gang had raided his more peaceful neighbours. In the course of subsequent proceedings he had treacherously killed a British officer, and a punitive expedition became inevitable. The greater part of the military forces of the Protectorate were engaged in police work on the north-eastern frontier; but they were hastily recalled, and within a month, thanks to Major Burnaby's energy, the punitive column was ready to start. The stores for the expedition were collected at rail-head, and the major had been very busy day and night in getting them up from the coast, and seeing that everything possible, to the smallest detail, was done to secure the safety and success of the column.

After the doctor had gone, the major sat for some minutes silently puffing his pipe, while Tom nervously turned over the leaves of a month-old copy of the Times. At length the major laid down his pipe, cleared his throat, and began:

"Look here, Tom, few words are best. I suppose you realize by this time that you did a very foolish thing in coming out. What's more, it was a very inconsiderate thing. Here am I, with my hands full, toiling day and night to straighten things out,--and you must come and complicate matters just as I'm driving in the last peg, and without a moment's warning; in fact, making an attempt to force my hand! It was silly, it was wrong, to say nothing of the waste of time when you ought to be working at your profession, and the waste of money which you know as well as I do you can't afford. There'd be a glimmer of excuse, perhaps, if I could make any use of you, and I'd stretch a point to do so; but it's entirely out of the question. I can't find any reason, not even a pretence of one, for bringing you in. There is really nothing for you to do. So there is no help for it, and, as you can't possibly stay here, and are bound to go back, you may as well go at once. If you really and seriously think of choosing Africa for your career, there'll be plenty of time to talk about that when you've finished your training; and we can go into it when I get home."

The major relit his pipe, and hid his sympathetic features behind a cloud of smoke. After a moment Tom said quietly:

"I'm sorry, Uncle. I didn't see it from that point of view. I was an ass. I'll go home and do my best."

"That's right, my boy," said the major heartily. "It's no good crying over spilt milk. I was young myself once; we all have to buy our experience, and 'pon my word I think you're getting yours pretty cheap after all."

He rose from his chair, and put his hand kindly on Tom's shoulder. "I'm going to turn in," he added; "have to be up at dawn. Call Saladin if you want anything. Good-night!"

During the next few days Tom almost forgot his disappointment, so much was he interested in watching the final preparations. There were boxes and bales everywhere. Empty kerosene cans were shipped on the launches, to be filled with water when the force began its land march. Boxes of ammunition, tin-lined biscuit-boxes of provisions, a tent or two for the officers, canvas bags and smaller cases for the medical stores, were carried on board on the backs of stalwart negroes, and all their friends and neighbours crowded around, gesticulating frantically in their excitement. It was all so novel that Tom had scarcely a minute to reflect on his hard luck; and, indeed, so far from sulking, he sought every opportunity of making himself useful, and was well pleased when he chanced to overhear his uncle one evening say to Dr. O'Brien:

"'Pon my word, Corney, I'm sorry we can't take the boy. I like his spirit. He's willing to turn his hand to anything, and has relieved me of quite a number of odd jobs during the past few days. But I don't see how we can possibly take him, and in any case he will be better at home."

The last day came. It was a fine Thursday in May. There was a crispness in the air that set the pulses beating faster and made life seem worth living indeed. Everything was done. The stores were well stowed on board, the fighting-men and carriers had answered the roll-call, and the major, with a final survey, had assured himself that nothing had been overlooked. The launches had been getting up steam for an hour or more, and the officers, having seen their men on board, were standing on the quay to take a farewell of the little group of Europeans assembled to wish them God-speed.

The whole population of the place seemed to have gathered to witness the start. Arabs in their long garments, turbaned Indians, and more or less naked negroes were mingled in one dense mass along the shore. Some of the natives had donned their best finery for the occasion. One old fellow appeared in a battered chimney-pot hat and a tattered shirt that reached his knees, with a red umbrella tucked under his arm. Others displayed plush jackets of vivid hue, and wore coral charms and bracelets round their necks and arms. Women with little brown babies filled the air with their babblement, and the noise was diversified now and then by the squealing grunt of camels and the whinnying of mules.

Tom was the last to grasp his uncle's hand.

"Good-bye, Uncle!" he said. "Good luck to you!"

"Good-bye, my boy! Sorry you aren't with us. But cheer up; please God, we'll have a good time together yet."

Then the gangway was removed, and, amid British cheers and African whoops, the launches puffed and snorted and glided away over the brownish waters of the great lake.

Tom heaved a sigh as he turned away.

"Well, well, that's over," said Mr. Barkworth, walking with Lilian by his side. "We haven't seen much of you, sir, since we came up on Monday. Never fear, your uncle will pull it off. I remember, now, at Calcutta, a year or two ago, he said to me: 'Barkworth, I'm going downhill fast. Here am I at forty-six the wretchedest dog in the service, with nothing but half-pay and idleness in front of me.' 'Cheer up,' said I, 'you'll get your chance. There is a tide in the affairs of men, you know. You'll be a K.C.B. yet.' I knew it, h'm!"

"I'd give anything to have gone too," said Tom.

Lilian looked amazed and shocked.

"Why, Mr. Burnaby, you might get killed!" she said.

Tom laughed.

"I'd chance that. Besides, I might not. Anyhow, it's better to be killed striking a blow for England than to peg out with pneumonia in a four-poster, or die of a brick off a chimney."

"Fiddlesticks!" said Mr. Barkworth. "Pure fudge! Gordon said something of the same sort to me once; I knew him--a sort of forty-eleventh cousin. 'Barkworth,' he said, 'Heaven is as near the hot desert as the cool church at home.' Now I'm what they call a globe-trotter, through this restless girl of mine here, and I tell you that when my time comes I shan't rest comfortably unless I'm laid in the old churchyard at home. H'm! But this won't do. We aren't skull and crossbones yet. Come and dine with us to-night, Mr. Burnaby; seven sharp; you'll meet a padre too; one of the White Fathers, you understand. Knows every inch of the country, and speaks the language like a native--only better. Lilian stayed for a year with some friends of his in France, and we brought out a letter of introduction. A fine fellow, this White Father--no white feather about him, ha! ha! You take me, eh! Well, then, we'll see you at seven. Mind you--seven sharp!"

Mbutu--Hatching a Plot--The Padre--A Consultation

The sun had set, and Tom was sitting in his uncle's bungalow, ruminating. He had changed his clothes in preparation for dining with Mr. Barkworth; but there was still nearly an hour to spare, so he sat back in his chair with his hands in his pockets and stared at his toes. In a few more hours he would be jolting down to Mombasa. There was no getting over that. He pictured his uncle penetrating the forest at the head of his men; the cautious advance; the first sight of the enemy. He heard in imagination the rattle of musketry, and the major's ringing voice giving orders and cheering the combatants. And while these stirring events were in progress, he himself was to be condemned to inactivity on a passenger steamer! Tom was hit harder than he had believed.

Sitting brooding on these things, and feeling the reaction doubly after the excitement of the past few days, he suddenly became fully conscious of a sensation that had for some time been creeping over him unawares. He felt that he was not alone, that someone was looking at him. There was no one with him in the room, he knew; no one in the bungalow even, except the grave, silent Indian servant, who was the only member of the household left behind.

"Rummy feeling this," said Tom to himself, pinching himself to make sure that he was awake. He jumped up and switched on the electric-light, and in the first flash thought he saw a black face pressed against the narrow window-panes. Instantly he ran to the door, flung it open, and returned in a moment with a woolly-pated black boy in his grasp. Gripping him firmly with one hand, he locked and bolted the door with the other, then loosed his hold and stood with arms akimbo.

"Now then, who are you? What does this mean?" he said.

The boy stuck his arms akimbo in imitation of Tom, grinned, and chortled rather than said:

"Me run away!"

"Oh indeed! Run away, have you? And where from, may I ask?"

"Me Mbutu, sah! Mbutu servant dago man; sah knock him down; me no go back--no, no; me hide; now me heah."

He chortled again with a childish air of satisfaction which made Tom smile.

"Oh! So you're the beggar I saved from the whip, are you? Well, my boy, I'm very glad to have helped you; but really I don't see what more I can do for you. Hungry, eh?"

"No, no."

"Well, then, what do you want?"

"Me and you, sah; you me fader and mudder, sah; all same for one; me stop, long stop."

"Oh, come! it's kind of you to say so, but I'm off to Mombasa to-morrow, and then home--over the big water, you understand. Don't want to adopt anyone yet, and can't afford a tiger."

The boy's face fell. Then he clasped his hands and poured out a rapid torrent of the queerest English, evidently an account of his career. Tom made out that he belonged to an ancient Bahima tribe, and was the son of a chief whose village had been raided by Arabs, all his people being killed or carried off as slaves. The boy himself, after two years of captivity, had escaped, through a series of lucky accidents, to British territory, and had since been more or less of an Ishmael, picking up a precarious living in doing odd jobs about the European bungalows. His last master had treated him with a brutality that recalled his years of captivity with the Arab slavers. Tom's short way with the bully had won the boy's unbounded admiration and gratitude. He had remained in hiding until he knew that the Portuguese had taken his departure, and then had felt that he could not do better than attach himself to his benefactor.

Such was his story, told disconnectedly, the English pieced out with occasional phrases in Swahili, the lingua franca of Eastern and Central Africa. Through all the narrative there was a convincing note of reality. The boy pleaded to be allowed to serve Tom for the rest of his life till, as he said, the "long night" came. He would not ask for wages, he could live on anything--nothing; and he flung himself down at Tom's feet, imploring him not to drive him away.

"Poor chap!" said Tom. "Sorry for you, but what can I do? My uncle wouldn't have me, or I might have made some use of you. And there's no chance now; he's away with the expedition to Ankori."

Mbutu's eyes opened to their fullest extent.

"Sah him uncle!" he cried.

He looked puzzled and anxious, and yet seemed to hesitate.

"Well, what is it?" asked Tom.

"Sah him uncle!" repeated the boy; and then, to Tom's amazement, he rattled off a story of how, some ten days before, he had overheard a conversation between his late master and the interpreter to the expedition.

"Palaver man bad man, sah. Much bad. Talk bad things. Say black man hide; white man walk so." He took a pace or two with head erect, eyes looking straight ahead, and arms straight down his thighs. "White man no see not much; bang! soosh! white man all dead."

Everything he said was illustrated with many strange pantomimic gestures, and Tom was at first puzzled what to make of it all. Then he set himself patiently to question the boy, using the simplest words, and from his answers he put together, bit by bit, a most astonishing story. About a fortnight before, the Portuguese had come with Mbutu from the forest west of the Nyanza, accompanied by an Arab, and had taken up his quarters in a small bungalow not far from rail-head. He was in and out all day, engaged in some mysterious business which the boy had never succeeded in fathoming, while the Arab had disappeared on their arrival in Kisumu. One hot night Mbutu, feeling restless and unable to sleep, went outside the bungalow with a pipe of his master's which he intended to smoke. He was fumbling in his loin-cloth for a match, when he saw a figure slinking cautiously towards him. His movements were so stealthy and furtive that Mbutu's curiosity was at once aroused. Unfortunately for the stranger, who clearly wished to escape observation, the moon was high, and Mbutu, concealed by a friendly post in the compound, watched him steal up to the bungalow, enter quietly, and shut the door. The boy, avoiding the patches of moonlight, crept round the veranda with the noiselessness of a cat till he came to a half-open window. A lamp was burning in the room, throwing a long beam of light into the darkness without, and in skirting this bright zone the boy tripped over an empty wooden crate from which the cook obtained his supply of firewood. The impact of Mbutu's shins against the sharp edges of the crate set the thing creaking, but the noise was drowned by the yelp of a jackal in a nullah hard by, and after a few moments of anxious suspense Mbutu breathed again. He peeped cautiously round the edge of the window. The room was empty, but as the light had not been removed Mbutu concluded that his master would soon return. This proved to be the case, for in less than a minute the Portuguese appeared, moved quickly to the window, and lifted the iron rod as though to close it. But the night was so hot that he changed his mind, comfort prevailing over caution. He left the window as it was, and simply lowered the blind. Then, turning to the door, he beckoned his visitor into the room. A thin beam of light still filtered between the bottom of the blind and the window-sill, and Mbutu's sharp eyes noticed that the sill was wide, projecting some inches from the wall. He saw that under this he could lie without fear of detection, and probably hear all that passed inside. So he crept beneath the shelter of the sill, and strained his quick ears.

For a time he could make out little of what the two men were saying. Then their voices rose, they became "much jolly", as he said, after the Portuguese had produced a flask of his own special brandy, and Mbutu heard every word distinctly. They were discussing a plan concerted between them during the journey to Kisumu, and congratulating each other on its success. The Arab, apparently, was connected with the chief against whom the punitive expedition was directed, and the dago having reasons of his own for desiring its failure, they had put their heads together. The result of their scheming was that the Arab had somehow got himself recommended to Captain Lister, the intelligence-officer of the expedition, as interpreter and guide, his real intention being to lead it into an ambush, cunningly devised between the chief and the Portuguese. The European officers were to be killed by picked marksmen in the first moments of confusion and the plotters hoped to lay their trap so carefully that not a soul would escape. What his master's motives were Mbutu had been unable to discover, though he had heard a mysterious reference to a store of ivory and a run of slaves. After a time the "special brandy" began to take effect, and both the men fell asleep. The light went out, and Mbutu stole away.

Tom only pieced this together by degrees. When the meaning of it all was clear to him, he gave a long whistle and stood staring at the black boy. Suddenly a suspicion flashed across his mind as he remembered what he had read of the imaginativeness of the African native and his genius for inventing fairy tales.

"You're not making this up?" he said sternly. "Why didn't you tell all this before the expedition started?"

Mbutu spread out his hands.

"What for good?" he said. "Me tell? White man say 'Bosh! Liar! Get out!'" He shook his fist and lifted his foot with the accuracy of long experience. "Mbutu no lub kiboko. White man all same for one."

He pointed expressively to the scars and weals left on his shoulders by his recent thrashings with the kiboko.

"Then why have you told me now?" demanded Tom.

The boy for a few instants looked puzzled; then his features expanded in a cheerful smile as he said:

"No kiboko heah, sah! Sah little son of big sah! Sah Mbutu him fader and mudder!"

Tom could doubt no longer; truth spoke in every line and dimple of the boy's earnest face. But what was he to do? Glancing at the carriage clock on the mantel-piece, he saw that it wanted only ten minutes of seven, the hour fixed by Mr. Barkworth for dinner. He wondered if he had better consult his new friend, for whom he had already begun to entertain warm feelings of regard. Calling the major's Indian servant, he gave the boy into his hands with instructions to keep a sharp eye on him, and hurried off, his brain in a whirl.

"Ah, here you are, then!" said Mr. Barkworth, coming forward as Tom entered the bungalow, and laying a friendly hand on his shoulder. "Punctuality, now; that's a fine thing. The padre came a moment ago. I'll introduce you, h'm!"

He turned and led the way into an inner room, where Tom saw a figure that would have commanded attention in any company. It was that of a tall man of about fifty years, with clean-cut features of olive hue, mobile lips with the fine curves of a Roman orator's, and grayish hair falling back in flowing lines from his temples. He was dressed in the simple white robe of an Arab, with no ornament save a small gold cross pendent on his breast. The simplicity of his attire served only to heighten the natural dignity of his bearing.

"H'm! Mossoo--Mossoo-- Now, what on earth's the French for Thomas! Mossoo Tom Burnaby, Père Chevasse. And a fine fellow, sir," he added to Tom, sotto voce.

The missionary smiled as he shook hands.

"I have seen you already," he said in French. "I was a spectator the other day of that little scene, Mr. Burnaby, when you played the part of Good Samaritan."

"Ah!" said Mr. Barkworth, catching the phrase. "Who's been falling among thieves, padre?"

The missionary briefly told the story of Tom's summary treatment of the Portuguese, and though Mr. Barkworth's French was decidedly shaky, he made out a few leading words here and there, and got a tolerable grasp of the incident.

"Well now, I call that fine," he said; "Rule Britannia, and all that sort of thing, you know. And what became of the black boy? I warrant, now, he never even said thank you. No gratitude in these natives; I know 'em."

Tom was on the point of confuting Mr. Barkworth with the best of evidence, but Lilian's entrance checked the words as they rose to his lips, and by the time they were seated at the dinner-table his host's volatile mind was occupied with other matters.

Looking back on this dinner afterwards, Tom wondered how he managed to get through it without breaking down. He listened to the quiet, mellow voice of the missionary, and envied the fluency of Lilian's French; he smiled inwardly at Mr. Barkworth's desperate efforts to follow the conversation, and good-humoured laughter at his own mishaps; he even made his own modest contribution, and, after the first moments of diffidence, was put quite at his ease by the Frenchman's perfect courtesy. And yet, all the time, through all the talk, he felt one sentence dinning and throbbing in his head: "What am I to do? What am I to do?" He imagined his uncle in the depth of the forest, fighting for dear life amid a horde of savage blacks, and overborne at the last by sheer weight of numbers! A cold thrill shot through him, and he started, to answer haphazard some remark from Lilian or the missionary, not knowing what he said. Once or twice Lilian looked at him enquiringly, wondering at his strange absent-mindedness, and then he collected himself with an effort and tried to appear unconcerned.

After dinner Mr. Barkworth settled himself in an easy-chair and lit a cigar, and while the others sat chatting together he dropped asleep. The missionary gave his listeners an account of the work of the White Fathers' mission to which he belonged, and chanced to mention an incident that had occurred among a Bahima tribe. Bahima! That was the name of the race to which Mbutu belonged. Tom knew that his time was come. Speaking as quietly as his excitement allowed, he told Mbutu's story. The missionary looked incredulous; Lilian's fair cheeks paled, and she cried:

"Oh, what a wicked, wicked thing!"

"Eh? What?" said Mr. Barkworth, waking with a start. "As I was saying, these natives never show any gratitude. Now I remember a case when I was in Trinidad. An overseer there--"

But Lilian had seated herself at her father's feet, and laid her hand on his knee.

"Father," she said, "Mr. Burnaby has some strange and terrible news to tell you."

"God bless my soul, you don't say so! What in the world has happened?"

"Mr. Barkworth," said Tom, "the boy I saved from the Portuguese came to me to-day and told me of a diabolical plot between his master and the dragoman of the expedition to lead my uncle into a trap. What can be done to warn him?"

"What! What! Ambush Jack Burnaby! Ridiculous nonsense! Never heard of such a thing. More like a bit out of Henty than a real thing. H'm! Come now, what did the young rascal say?"

Tom repeated the story, giving, as nearly as he could, the minutest details told him by Mbutu.

Mr. Barkworth took out his handkerchief and blew his nose. "H'm! Cock-and-bull story altogether. I know these natives. Taradiddles, sir!"

"But why doubt the boy, sir? His story was so circumstantial, and he looked so earnest and truthful."

"H'm! What do you say about it, mossoo?"

"It is extraordinary, certainly," replied the Frenchman. "Could we not send for the boy? He would not try any tricks with me."

"Right! we'll have the boy. Fine thing--a knowledge of their gibberish. Hi, you there! Go down at once to Major Burnaby's bungalow and bring back the black boy there. Clutch him by the hair or he'll wriggle away. I know them."

One of the servants disappeared, and soon returned with Mbutu. The boy had been waked out of a sound sleep, and looked rather scared, but a few words in his own tongue from the missionary soon put him at ease, and he answered all his questions readily. After a searching examination Father Chevasse turned to Mr. Barkworth, saying:

"The boy's story is consistent in every part. I think he is telling the truth."

"Well, you ought to know, padre. What's to be done, then? We can't let a fine fellow like Jack Burnaby be snuffed out by a parcel of heathens. Suppose we tell the man in charge here--Captain Beaumont, isn't it?"

"Little use, I am afraid. Captain Beaumont doesn't understand the natives; and I fear he would scoff at Mbutu's story and refuse to believe it. The boy has an animus against the dago, you see."

"Why couldn't I go after the expedition myself along with Mbutu?" broke in Tom eagerly.

Mr. Barkworth looked dubiously at him, as though he half suspected for an instant that the story was got up for the occasion. But a glance at the young fellow's anxious face made him repent at once. He blew his nose again and said:

"I'm an old fool, h'm! Well now, let's talk it over."

A long and serious discussion ensued, in which Tom and Mr. Barkworth bore the greater part.

"Well, well," said Mr. Barkworth at length, "have your own way. Yes, my boy, you must go. You have a valid reason--the strongest motive anyone could have. And your uncle, sir--begad, if he takes you to task for disobedience, why, just refer him to me, and say that I'll get Tommy Bowles to ask a question in the House. I know him!"

"But how can Mr. Burnaby go after them?" put in Lilian. "They have taken all the launches, I know."

Mr. Barkworth's countenance fell.

"Whew!" he ejaculated. "That's a facer! Never do to go on foot, Tom; never overtake 'em in time round the north shore. H'm!"

"I have a launch," said the missionary quietly. "Quite a small thing, steaming only a few knots. I am starting to-morrow to visit our station at Bukumbi, at the other end of the Nyanza, and if Mr. Burnaby cares to come with me, I can take him on afterwards to the river for which the expedition is making."

"Couldn't you go straight across, sir?" asked Tom eagerly. "You see how important it is to lose no time."

"I am sorry I cannot. I have important letters from my superior to the father in charge of the mission, and I am bound to deliver them at once. Besides, not much time will be lost. The launches are calling at Entebbe to pick up a draft of the King's African Rifles, so that we shall probably be only a day behind them, and you should overtake your uncle some days before he reaches the place where the fighting will begin."

"What's he say, Lilian?" said Mr. Barkworth in a stage whisper. "Capital!" he cried, when she had briefly explained; "his head's clear enough for an Englishman's. Close with Mossoo's offer, Mr. Burnaby. Ask the padre what time he starts, Lilian; for the life of me I never can think of the French for start."

"At eight in the morning," said the missionary. "If all goes well we shall cover a hundred miles before we anchor for the night."

"Well, now, that is what I call business. Now, Tom, you'll be ready at eight with this Booty, or whatever you call him, and I'll be there to see you off. Gad, if I hadn't a girl to drag me about I'd come too, though I'm sixty-three next week. Now, good-night, my boy, and God bless you!"

Tom gripped the old gentleman's hand warmly, and after wishing Lilian good-bye, went off with the White Father to talk over their plans and trace out their route before turning in for the night.

Tom's First Crocodile--Night on the Nyanza--In German Africa--A Storm on the Lake--A Short Way with Hippos--Danger Ahead

Long before eight next morning Tom was down at the quay examining the launch in which he was to begin his pursuit of the expedition. His inspection made him feel rather unhappy.

"Why, she's nothing but a crazy old tub," he said to himself ruefully. "Planks half-rotten, rudder stiff, and looks as though she hadn't seen paint for an age. Lucky this isn't open sea, for anything like dirty weather would just about finish her ramshackle engines. Well, let's hope for the best."

He returned to the bungalow, where with Mbutu's assistance he made his final preparations. These were not elaborate. The padre had advised him to travel as light as possible, taking merely a few articles of underclothing and other necessaries, with the addition of a couple of hundred beads and some yards of calico, the common articles of barter and sale in the interior, in case he had to purchase food from the natives during the final stage of his journey. Luckily there was a fair stock of these in the bungalow. Tom had of course discarded his straw hat long before, and now wore a white solah helmet, which could be relied on to protect him from the mid-day sun. He had found an old rifle of his uncle's, and a case of cartridges, which he thought it advisable to take. He ate a light breakfast of fried fowl capitally prepared by the Indian, gravely acknowledged his salaam, and then, giving Mbutu the baggage to carry, started for the quay.

The missionary was already on board, and steam was up, but there was no sign of Mr. Barkworth. Tom wondered whether he had forgotten his promise to see him off. Just as he was about to go on board, his genial friend appeared in the distance, hurrying at a great pace towards the quay, flourishing a red bandana. Tom was surprised, and secretly not a little pleased, to see that Lilian was with her father.

"Here we are," cried the old gentleman, puffing and gasping as he came up. "All on board, h'm? Got everything you want? Now, whatever you do, don't get your feet wet! And look here, here's something I warrant you've forgotten. Writing-paper, eh? Ink too. Let us know how you get on. Any black 'll carry a letter for you for a few beads. My girl will have dragged me off to the ends of the earth long before you get back, but remember we're always home for Christmas. Glad to see you at the Orchard, Winterslow, any time. Now, then, good luck to you, and God save the King!"

Mr. Barkworth shoved a folding writing-case into Tom's left hand, gripped his right heartily, and waggled it up and down till he was tired.

"Good-bye, Mr. Burnaby!" said Lilian, "and I do hope you will succeed."

Tom shook hands, lifted his hat, and stepped on board. The crazy engine made a great fluster as it sent the screw round; the launch sheered off, and Tom stood side by side with the padre, watching Mr. Barkworth waving his hat and Lilian her handkerchief until they were out of sight. After seeing that Mbutu was safe in the company of the native stoker, who formed the whole crew of the little vessel, Tom placed a camp-stool under the awning by the side of the missionary's deck-chair near the steering-wheel, and looked about him.

The launch was cutting its way slowly through the brown sluggish waters of Kavirondo Bay. The shore was flat and uninteresting, part bare rock, part rank marsh, spotted here and there with sacred ibises in their beautiful black-and-white plumage. At several points along the bank Tom saw a huge plant like an overgrown cabbage run to stalk, or rather to many stalks, sticking out of a short swollen stem, like the arms of a candelabra. This, the padre told him, was the candelabra euphorbia, a plant of which the natives stood very much in dread, because its juice was highly poisonous, and because it was so top-heavy and so loosely rooted that in a high wind it frequently toppled over, with damaging effect to anything that might be within its shade.

As they emerged from the bay into the open lake, the water changed its brown to a deep and beautiful blue, and the shore became more interesting. The lake here was fringed with a thick growth of rushes--long smooth green stems crowned by a mop-head of countless green filaments becoming ever finer and more silky towards the end. Amid the vegetation appeared the forms of whale-headed storks with yellow eyes, and gold-brown otters with white bellies darted in and out among the rushes. There was a light wind off-shore, and Tom had a distant view of many wild denizens of the lake country, which would otherwise have been alarmed by the throb of the engines. His companion lent him a field-glass, and for hours he revelled in the panorama of tropical life that passed before his eyes. At one point he saw an antelope come down a wooded slope to the edge of the water. What seemed to be a green moss-covered log of wood lay almost hidden from the animal by the bulging bank. The antelope had just put his fore-feet into the water when the log moved, one end of it parted into two yawning jaws, and for the first time in his life Tom saw a crocodile in its native element. The trembling antelope started back, just escaped the snap of the huge hungry jaws, and bounded back into the forest.

Tom could not resist the temptation to try a shot at the slimy reptile. He took careful aim and fired. The crocodile slid off the half-submerged sand-bank on which it was basking, and disappeared in the water.

"Did I hit it, sir?" he asked eagerly.

"It is impossible to say. It may merely have been startled by the report, and we could only make sure by waiting to see if its body rises."

"And that, of course, we can't do," said Tom with a sigh.

The launch sped on and on, steaming now her full seven knots. Tom noticed that she was never very far from the land, and knowing, from his look at the map overnight, that Bukumbi was almost in the centre of the southern shore, he wondered why the padre did not steer a more westerly course. He asked the question.

"Well," said the missionary, "it is partly custom and partly superstition, I suspect. Everyone is shy of sailing directly across from north to south or east to west. Many of our launches are hardly tight craft, as you see, and a storm would be a very serious matter in the open."

"But surely there are no storms on an inland lake?"

"There are indeed. The wind here sometimes lashes the water into waves as high as any you can see on the English Channel. Gales have blown the native dhows out into the open, and they have never returned. The natives, too, will tell you that a huge monster inhabits the waters near one of the many islands that stud the lake; there it lies in wait to suck their craft down. I have never seen it myself," he added with a smile, "but I once heard your Sir Harry Johnston say that he had looked into the matter, and was rather inclined to believe that the monster was a manatee."

Still they sailed on. After sixty miles or so they left British territory and came into German East Africa, and soon the tropical forest which had clothed the highlands sloping back from the shore, gave place to more level grassland, some of which was evidently under cultivation. The shore was indented in many narrow creeks, and in one of these Tom saw a singular-looking canoe, at least fifty feet long, manned by a dozen naked Baganda. The keel of this, the padre told him, was a single tree-stem, the interior of which had been chipped out with axes and burnt out with fire. When the keel was finished, holes were bored in it at intervals with a red-hot iron spike; the planks for the sides were similarly pierced; and then wattles made of the rind of the raphia palm were passed through the holes, and planks and keel were literally sewn together. All chinks and holes were then stopped with grease, and the whole canoe, inside and out, was smeared with a coating of vermilion-coloured clay. The prow projected some feet beyond the nose of the boat, and sloped upwards from the water. The top of it, Tom observed, was decorated with a pair of horns, and connected with the beak by a rope from which hung a fringe of grass and filaments from the banana-tree. When the occupants of the canoe caught sight of the White Father, they struck their paddles into the water, and drove their slender craft rapidly towards the launch. But the padre made signs that he was in a great hurry and could not stop to speak to them, and after a time they desisted and paddled back to the shore.

"Though I believe they could have overtaken us if they chose," said the missionary. "I have known them propel their canoes at six or seven miles an hour."

"Mr. Barkworth would call them fine fellows," remarked Tom with a smile. "I always had an idea that the natives of these parts were a puny, stunted set of people, but really those fellows in the canoe are splendid specimens."

The sun set, and the moon rose, and still the launch panted along. At last, when it was nearly ten o'clock, and the log showed close upon a hundred miles, the padre ran the boat into a wide creek, where he anchored for the night.

Tom looked weary and heavy-eyed when he greeted the missionary about six o'clock next morning.

"Your wild neighbours are rather too much for me," he said. "I did not sleep a wink till near daylight. Never in my life have I heard such weird noises."

"And I slept like a top," said the padre, smiling. "What were the noises that disturbed you?"

"Well, there was, for one thing, the squawk of the night-jar, which was unmistakeable; then there was the croak of frogs, only this was louder than our English frogs can manage, just like the sound of a gong beaten slowly. But there was a curious chirping, like a lot of bells very much out of tune jingling at a distance. What was that?"

"That was made by hundreds of cicadas in the reeds."

"Then an owl hooted, and some old lion set up a roar, and then again there came a strange bark I never heard before; it began with a snap, and rose higher and higher in pitch, till it became a miserable howl that gave me the shivers."

"That was the jackal."

"An eerie brute," rejoined Tom. "One answered another until there was a whole chorus of them at it, all trying to howl each other down. But worst of all was a dreadful squeal, just like a baby in mortal pain. I was dozing when I heard that; I became wide-awake with a start, and jumped up, and then remembered where I was. It couldn't have been a baby, could it, Padre?"

"No; it was no doubt a monkey which had climbed down from the branches of some mimosa, and found itself in the coils of a snake. You will get used to that sort of thing if you spend many nights in Uganda. But now, steam is up, I see; we must be off."

"There is one thing that has been puzzling me," said Tom. "Last night you told me we were now in German East Africa. But how is it that you have a French mission in German territory?"

"The explanation is simple. We were here before the Germans. This great lake was discovered by your Captain Speke in 1858, you remember, but it was not until Stanley came here in 1875 that the attention of Europe was really called to Uganda. You have heard, no doubt, of Stanley's famous letter to the Daily Telegraph, asking for missionaries to be sent out here?"

"I can't say I have."

"Well, when Stanley came, he found the king, Mtesa, much perplexed about religious matters, and he wrote a letter asking that English missionaries might be sent out to evangelize the people. A friend of Gordon's, a Belgian named Linant de Bellefonds, happened to be here at the time, and he volunteered to take Stanley's letter to Europe by way of the Nile. On the way, poor fellow, he was murdered by the Bari, who threw his corpse on to the bank, where it lay rotting in the sun. An expedition sent to punish the Bari found poor Bellefonds' body, and on removing his long knee-boots they discovered the letter tucked in between boot and leg. It was sent to Gordon at Khartum, and thence to England, and thus it came about that your Church of England mission began its work in Uganda in 1877."

"But how did you come here?"

"Oh, our mission, as I told you the other night, was started by Cardinal Lavigerie at Tanganyika. He thought that France should not be behind England in good works, so he sent some of his White Fathers northward to Uganda, and that is how we came to have a station at Bukumbi."

"What about the Germans, then?"

"After the missionary comes the trader. Your Joseph Thomson was the first to prove what splendid commercial prospects Uganda presented, and then, of course, there was a scramble. It would be too long a story to tell you of treaties and schemes; of the fickleness and treachery of the vicious King Mwanga; of Lugard and Gerald Portal and Sir Harry Johnston. But in 1890 Central Africa was parcelled out among Britain and Germany and the King of the Belgians, and you British, with your genius for colonization, have really done wonderful things. I admire your success; and there is one thing at least in which you and we are quite agreed--we both detest slavery, and the slave knows that whether he flies to the British trader's bungalow or the mission-house of the White Fathers, he is sure of protection."

The day passed uneventfully. Tom went down once or twice to relieve the native at the engine, and after what the missionary had told him of the storms that sometimes arose on the lake, he hoped more than ever that the crazy machinery would be equal to the strain put upon it.

About seven in the evening the launch came to the mouth of the Bay of Bukumbi. There was a good deal of sea running, and it took the Father, with Tom's assistance, more than half an hour before they found, in the darkness, among the tall swishing reeds, a place where they could land. The task was at length accomplished; leaving Mbutu and the stoker on board, the padre and Tom went ashore, and met with a warm welcome from the fathers at the station. They dined and slept at the mission-house, and left early next morning, taking some fresh food on board. Father Chevasse wished to make direct for the Sese Islands at the north-west of the Nyanza, where the White Fathers had another station, but he found it necessary to put in for fuel at Muanza, some two hours' sail from Bukumbi. While he went to visit an acquaintance there, Tom strolled about the station, wondering at the bare and desolate appearance of its surroundings. He learned afterwards that the Germans had cut down the trees and burnt the villages within five miles of their fort--an infallible specific for keeping the country quiet. As he sauntered along he was half-startled, half-amused, to hear a native servant addressing a young subaltern, evidently fresh from the Fatherland, in a queer jargon of broken German. The effect was even more ludicrous than the broken English of Kisumu.

Tom's next impression was of a different kind. Turning into a narrow thoroughfare off the main street, he came face to face with a German captain in full uniform, swaggering along with elbows well stuck out, and two inches of moustache stiffly perpendicular, militant and aggressive. There was very little room to pass. The path was narrow; on one side was a wall, on the other a muddy road very badly cut up by cart-wheels. It was clearly an occasion for mutual concession. But the German does not go to Africa to make concessions, Tom was obviously a civilian, and, by all the rules of the German social system, beyond the pale of military courtesy. To the German officer it was as if he were not there. The captain came on with the rigid strut of an automaton, taking it for granted that Tom would efface himself against the wall. But he had failed to recognize that the civilian was not a German. Seeing that a collision was inevitable, Tom conceded the utmost consistent with self-respect, and stiffened his back for the rest. There was a sharp jolt; the automaton, inflexibly rigid, swung round as on a pivot, clutched vainly at Tom for support, and subsided into the mud.

"Sorry, I'm sure," said Tom blandly. "Hope you're not hurt. The path is narrow."

White with anger, the German sprang to his feet, and, with the instinct of one not long from Berlin, laid his hand on his sword. But the tall figure walking unconcernedly on was unmistakeably that of an Englishman, and the angry captain scowled ineffectually at Tom's back, and made a hasty toilet before starting to regain his bungalow by the less-frequented thoroughfares.

The padre was vexed when Tom told him of the incident.

"It was Captain Stumpff," he said, "commandant of the German station at Fort Bukoba near your frontier. He has no love for you English, and now he will like you less than ever. Not that his friendship is worth much. He is a boor, and a terror to the natives. The Germans are so much hated that the natives about here call them Wa-daki, 'the men of wrath', and well they deserve the name. Even the Portuguese are mild by comparison, and that is saying a good deal. Now as regards our journey, as we have been delayed at Muanza longer than I anticipated, I propose to steer straight across instead of hugging the shore. The weather is fine, and we shall save time in that way."

The launch went ahead at full speed, passing within about half a mile of the wooded island of Kome. Tom again found plenty of use for the field-glass, watching the myriad water-fowl of all descriptions that haunt the reedy shore of the lake. The air was beautifully clear, and if his mission had been less urgent Tom would have dearly liked to explore some of the creeks, fringed with tropical vegetation, that run up seemingly for miles into the land.

Gradually, however, they left the shore behind, and in a few hours the coast-line was but a hazy fringe on the horizon. They were by this time well out on the Nyanza, and the padre noticed with concern that the sky toward the north-east was assuming a leaden hue. The wind had freshened from the same quarter; the surface of the lake was changing; white-tipped waves came rolling up on the starboard side. In a few minutes, as it seemed, the sky became black; and then, with a sudden gust, a terrific storm of rain burst over the boat, drenching Tom and the missionary to the skin. The wind blew with ever-increasing force, sweeping the rain in sheets before it; the sea was being lashed to fury, and big waves broke with a swish over the deck. It was all that the men could do to keep their feet. Mbutu, perturbed both in body and mind, clung desperately to the handrail of the companionway; the native stoker was beside himself with terror, and in no condition to execute an order even if he could hear it above the tumult of the gale. The padre, wholly occupied with the wheel, shouted to Tom to keep an eye on the engine. Creeping across the deck, Tom made the best of his way below, with some difficulty closing the hatch above him. Just as he secured the hatch, a huge sea broke over the vessel, carrying away deck-chair and camp-stool, snapping the stanchions of the awning as though they were match-wood, and sweeping the ruins into the sea, among them the rifle which Tom had stood against the gunwale.

Having tumbled rather than run down the companion-way, Tom staggered to the engine and examined the gauge. He thought it possible to crowd on a little more steam, and as there was no chance of consulting the missionary, on his own responsibility he flung more logs on the fire. Meanwhile the boat was rolling and pitching terribly; every moment a heavy thud resounded as a wave broke on the deck; and Tom could hear the straining of the rudder as the missionary strove to keep the vessel's head to the wind.

The fight had gone on for an hour or more, when all at once the screw ceased to revolve; there was an escape of steam; and Tom knew that what he had for some time been dreading had at last occurred. The engine had broken down. Reversing the lever he clambered on deck, and saw by the expression in the padre's face that he knew what had happened. The downpour had ceased, but the wind was still blowing a furious gale, and, with no way on the boat, the rudder was useless.

"What is to be done?" shouted Tom in the padre's ear.

"Nothing. We are bound to drift; we are already driving towards the shore. Heaven send we miss the rocks!"

Both men clung to the wheel, and watched anxiously as the launch, shuddering under the waves that struck her in close succession, drew nearer and nearer to the shore. Tom could already see the foaming breakers rolling wildly against a huge rock that loomed up a hundred yards ahead. A few seconds more, and he expected the keel to strike. The missionary was alive to their imminent peril. Cutting loose a light mast, he hurried with it to the port side, and just as a wave smote the vessel on the other quarter, lifting it almost on to the rock, he thrust out the mast and pushed with all his might. Tom gave a gasp of relief. The vessel shaved the rock by a hand's-breadth, and sped past. A second later it was brought up with a sudden jerk, plunged forward a few yards, and then came finally to a stop.

"We are on a sand-bank," cried the padre. "If the storm continues we shall be broken up in half an hour."

"Can't we do anything, sir?" asked Tom.

"Nothing but trust to Providence."

Happily, not many minutes after the launch had grounded, the wind began to lull, and by the time it was dark had entirely fallen. With the suddenness characteristic of storms on the Nyanza, the force of the breakers rapidly diminished, the sky cleared, and the stars came out.

"I'm going down to see what's wrong with the engine," said Tom, dripping wet as he was. Fortunately he found a candle and dry matches. He struck a light and crept into the machinery. Ten minutes' examination showed him that the strain had loosened the valve connecting the steam-pipe with the cylinder, so that the pressure was inadequate to move the piston-rod. He had sufficient experience to know that he could repair it well enough to stand for a day or two. Coming out again he ordered Mbutu and the stoker, now recovered from their fright, to bale out the water that had shipped below; then he stripped off his clothes and wrung them out, dressed himself again, and set about his task.

By this time it was eight o'clock in the evening. The padre, having dried his clothes as well as he could, went below to see if he could lend Tom a hand; Tom thanked him, but said he thought he could manage by himself, and suggested that the missionary might order Mbutu to prepare some supper. In about three hours Tom came on deck tired and dirty.

"It's done, Father," he said. "The old thing's patched at last. It will stand till you get back to Port Florence, I think."

"Well done, Mr. Burnaby!" returned the padre. "It is wonderful good luck that I had such a skilful engineer on board."

"Well, you see, I had some experience in Glasgow," said Tom modestly. "And then the chief engineer on the Peninsular showed me all over his engines, and taught me a lot. Shall we fire up to-night?"

"No, I think we'll lay by till morning and get what sleep we can. Then I hope with the dawn we shall be able to run off the sand-bank. I have made some cocoa, and I am sure you must be hungry."

Tom was so fatigued that as soon as he laid his head down after a good meal he fell asleep. Five hours slipped by like twenty minutes, and then he was awakened soon after daybreak by a loud snorting bellow that seemed to shake the vessel. Bounding on deck he found the padre already there, looking with dismay at a crowd of hippopotamuses sporting in their lumbering way among the rushes. The animals appeared to have just discovered the launch, and to have decided that it was an intruder into their domains, to be summarily ejected, for one great bull lifted his thick snout and, furiously bellowing, charged. The impact stove in a plank just above water-line, and lifted the vessel half out of the water. The stoker yelled with terror. Mbutu snatched up the mast that had proved of such good service the day before, while the padre looked anxious. There were no arms on board, and Tom bitterly regretted that he had not left his rifle below instead of keeping it with him on deck. Suddenly an idea struck him. Placing his hand on the funnel he found, as he had hoped, that the engine-fire was alight. He ran below, picked up a length of hose he had noticed coiled near one of the bunkers, fixed one end to the exhaust-pipe, and hurried back to the deck, carrying the nozzle end with him. Instructing the stoker to turn on the cock at a signal, he went into the bows and saw the hippo preparing for a second charge. Shouting to the stoker, he pointed the hose full at the eyes of the gigantic beast; a stream of boiling water issued from it, and the hippo, bellowing with pain, plunged off the bank with a force that shook the vessel, and lumbered away. His companions watched him for a few seconds with a look of dull amazement, and then, taking in the situation, stampeded after him.

"The enemy retires in confusion," said Tom, laughing.

"A capital idea of yours," said the missionary. "I confess I was really somewhat alarmed. After all, I believe the brute has helped us. I fancy he shifted us a little off the bank. Put on the steam, and let us see if we can move."

Tom went below and pressed the throttle. The vessel did not stir. There was not sufficient depth of water. Hurrying on deck again he asked the padre to push from the stern with the serviceable mast; and after a few minutes' hard shoving at various places, he had the satisfaction of feeling the launch move an inch or two forward. Returning below he started the engine, and ten minutes later the boat slid off the sandbank into deep water. Fortunately no harm had been done to the bottom. The engine worked well, though Tom did not venture to put it at full speed after the strain of the previous day. Skirting the western shore, the vessel passed Bukoba in the afternoon, and about five o'clock arrived at the mouth of a river emerging into the lake through dense forest.

"This is the Ruezi," said the padre. "The expedition has gone up this river. I am glad, my dear boy, that in God's providence I have been able to bring you safely to this point, and I don't forget how much we all owe to your skill and presence of mind. Now I must land you here. I can take you in until the water is shallow enough for you to wade ashore. You will find a village half a mile or so inland, and your future course must depend on what information you there obtain. I am not very clear about the nature of the country, but the expedition will have left very distinct traces. I need not say I wish you every success, and on your return I shall hope to see more of you."

"Many thanks for all your kindness, Father!" said Tom, shaking hands warmly. "I'll look you up, never fear."

"Take my field-glass; you may find it useful," said the padre. "I have already packed up some tea and a few other things for you, and Mbutu has a couple of rugs; you will find nights in the open rather cold. Good-bye, good-bye!"